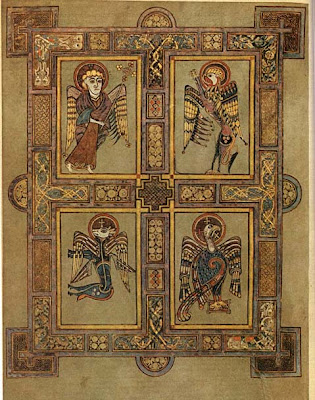

Images described by Ezekiel representing The Four Evangelists in the Book Of Kells

You've got your Greek Orthodox Church, you've got your Russian Orthodox Church... You've got your Serbian, Bulgarian, and Albanian Orthodox Churches... You've got your Assyrian Orthodox Church and your Egyptian and Ethiopian Coptic Orthodox Churches too, but the Celtic Orthodox Christian Church? That was a surprise to me. Who knew? Who knew there was such a thing?

Is this on the level? Actually, this group looks a little strident to me, and a little bit peevish and cavalier about their canonical status. There is in fact such as thing as the British Orthodox Church, but that was a mission inaugurated in the 19th century, and is representative of something else altogether.

The idea, however, is not as far fetched as it sounds. Although I'd put early Celtic Christianity firmly in the Catholic tradition, with the local Celtic Churches coming to an accomodation with the Roman mission at the Synod of Whitby (an accomodation which did eventually lead to the decline of a distinct Celtic spirituality), there are quite a few parallels between Celtic Christianity and Eastern Christianity.

Both the Celtic traditions and the Eastern traditions held a deep respect for mysticism, the relative independence of local churches within a greater whole, and of the monastic spirituality of the Desert Fathers. Also, very much like the the Eastern Church, the Celts considered themselves to be solidly in the tradition of John the Beloved Disciple, "listening for the heartbeat of God in all things." As this website, St Fillan's Celtic Apostolic Church (less strident than the one mentioned above) says:

Unlike most Western churches, the Celtic Church follows, and has always followed, the tradition of Saint John, that beloved disciple who leaned against the breast of Jesus, "listening for the heartbeat of God", at the Last Supper. This 'way of seeing' led to the Celtic Church's stream of spirituality which teaches that God may be found, heard and experienced everywhere and in all things and that a true worship of God, therefore, can neither be contained within the four walls of a sacred building nor restricted to the boundaries of religious tradition. Every blade of grass, every sigh of the breeze, every splash of rain, every wave of the sea, every movement of the earth, every flutter of a bird's wing, every twinkle of a star, every ray of sun... and every breath of man contains the very life of God. This was not only an early Christian way of thinking but also a Druidic belief, which may help to explain why, according to a number of legends, a lot of the Druids were so quick to accept Christianity after the arrival in Britain of the Apostles. It may also help to explain why some of the Druidic teachings were incorporated into the early 'Celtic Church'.

Christianity came quite naturally to the Celts (the Galatians to whom St. Paul wrote were Celts). Under the Druids and the Bards in Britain and Ireland, there was already a tradition that revered the spoken word, and was amenable to monasticism, asceticism, celibacy under certain circumstances, and a love of teaching in triads, which lent itself very well to the doctrine of the Trinity. Although there certainly must have been some tension with the Druids, the Celtic world of Britain, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland accepted Christianity quite peacefully. In Ireland, for example, there is no record of any Christian martyrdom during that island's conversion.

The Celts also had a profound love of nature, and felt very close to it, looking for the fingerprint of God in all created things. They incorporated this readily into their Christian spirituality, and in this respect they ran into some tensions with the Latin Church, which had adopted the Roman Law Court view of looking at the things, had a more pessimistic view of fallen world, and was heavily concerned over controversies related to Grace and Sin which did not carry the same imperative in the Eastern Churches and the Celtic Churches. The Latin Church tended to look at the Celts skeptically as possible Pelagians and pantheists .

The Celtic Briton monk Pelagius ran afoul with St. Augustine and St. Jerome, with Jerome nastily describing him as "that big fat fellow... walking with the pace of a turtle... bloated with Scots porridge." Eventually, Pelagianism was condemned as heresy, as well as Semi-Pelagianism, as was allegedly taught by John Cassian among the Celts in Gaul. Celtic teachers were suspect for their positive view of nature right up through John Scotus Eriugena, whose name basically translates to "John the Irishman from Ireland".

It would be an intriguing thing to post about in and of itself, if Pelagius was actually guilty of the real heresy he was charged with. Pelagius may have had too optimistic a view of human nature, and attributed too much to man’s free will, but I think he had a kernel of truth in at least this much – He maintained that creation is essentially good, and that to look into the face of a newborn is to look at the image of God. I ask you - when you look at the face of a newborn child, do you see the image of God, or do you see, like the Augustinian-influenced Calvin, a totally depraved creature, a hatchling chick that would gladly pluck out the eyes of another hatchling?

Father Timothy J. Joyce O.S.B. is the prior of Glastonbury Abbey in Hingham Massachusetts. He wrote a very good book a few years ago called Celtic Christianity. A Sacred Tradition, a Vision of Hope. I recommend it highly, and quote from it here at length:

Under the influence of Augustine the theology of the West concentrated more and more on issues of sin and grace. Thanks to Tertullian Western theology had already begun to become more legal in nature. The Celtic church did not get embroiled in the same issues. This early church was influenced significantly by the Eastern Christian churches of Asia Minor. Through trade there were even direct contacts with the East. Knowledge of the churches of both Jerusalem and Constantinople was widespread. The way of the early desert monks was emulated in Ireland, where the desert figures of Saints Paul and Anthony would be found on many high crosses showing the special devotion they enjoyed. The Celts already shared some cultural affinity with the East in music and myth.

The Christian faith primarily came to Britain from Gaul and then from Britain to Ireland. Surprisingly we find that there were a number of Eastern cults flourishing in Gaul at the end of the first century. The names of the earliest Christians in Gaul appear to be Greek and Oriental. The first bishop of Lyons, presumably the main Christian center in Gaul, was Pothinus (87-177). He came from Asia Minor, as did Saint Irenaeus of Lyons (130-200), who succeeded him as bishop from 178 through the year 200. Irenaeus was a significant person in early Christian theology. He had been a protege of Saint Polycarp, himself a disciple of John the Evangelist. The Johannine influence seems evident in Irenaeus and, it is suggested, through him to the Celtic church. Irenaeus lamented that he was in exile among the Celts, but his own theology of wholeness and his respect for the goodness of creation was in harmony with the Celtic worldview.

Another connection to the East came through John Cassian (360-435). Possibly born somewhere in the area of the Baltic, John entered a monastery in Bethlehem and later lived the monastic life in Egypt. From this firsthand experience of Eastern monasticism, he came to Marseilles in Gaul, where he founded two monasteries about the year 415. His writings on the monastic and ascetical life had a large impact in the West, including the influencing of the Rule of Saint Benedict (480-560) in Italy, soon to dominate Europe. John Cassian also influenced the development of monasticism among the Celts. Monasticism would soon in fact become a major aspect of the Celtic church.

Gallarus Oratory (Séipéilín Ghallarais), Dingle Peninusla, Ireland 6th-9th Century.

The Celtic church developed in its own unique way, absorbing much of its pagan antecedent. The relation of this church to Rome and the larger universal church emerges as an issue, especially for those who see the Celtic church as something distinct from the church of Rome. I find that this relation is sometimes reduced to a simplistic black-white, good guys-bad guys scenario. I do not believe the Celtic love of paradox and mystery, of unity in multiplicity substantiates such an approach. Neither do the facts of history. On the continent many Celts had embraced much of Roman culture without much resistance after Roman imperialism had spread its way northward. The relation of Celt to Roman was not always adversarial. As far as the Roman church was concerned, the Celts accepted its reality as the communal expression of the faith and embraced being part of the one Catholic Church.

There is no doubt, however, that the Celtic church then developed in a distinct way. The Celtic church in most of Britain would give way to both the new Anglo-Saxon culture and the church customs brought by Saint Augustine (of Canterbury) and the missionaries sent by Pope Gregory from Rome. Scotland and Wales, however, remained too remote for either of these influences to have their full effect. Celtic enclaves in these two areas of Britain remained Celtic. But, most significantly, the planned Roman invasion of Ireland never took place at all. The Irish were never part of the Roman empire nor exposed to its day-to-day ways. On the continent, the church spread with the empire and took on many of its organizational attributes. The system of dioceses with bishops as overseers was developed along with the urban spread of the empire, a diocese being set up in each urban setting. As the empire crumbled the church organization was often the only way to keep things together, and bishops emerged as administrators, stewards of people's needs, slowly acquiring a base of power and authority. The bishop of Rome was the exemplar of this development. But in Ireland, and largely in Scotland and Wales as well, there were no urban centers. Bishops and priests there did not acquire such power bases. The base there was communal, and abbots and abbesses emerged as leaders. The model was not hierarchical as the Roman one was, but more communitarian and relational. Women continued, at least in the earlier years, to have positions of authority and leadership and enjoyed equal rights. There is evidence, for instance, of groups of deaconesses called Conhospitae, who had a liturgical role in the Eucharist.

Some of the theological problems that beset Rome never impinged on the Celtic church. Saint Augustine, for an example, had come from a sect called the Manichaeans. This group held a dualistic view of reality, believing in a cosmic split of light and darkness. Material beings, including the human body and sexuality took on the aura of evil. There has been a recurring tendency to this belief in Christianity. It emerged earlier among Gnostics and would emerge again later in Albigensianism and Jansenism. This mindset never entered the Celtic Christian church (though it would affect Irish Catholicism at a much later date). The Celtic belief in the goodness of creation and all material being was too strong for this.

To sum up, I believe that the Celtic church had a freedom of expression in its history that led to practices unlike those of the Roman church; nevertheless it never believed it was not part of that church. It was a local church that was in communion with all other local churches forming the universal church with the bishop of Rome, who enjoyed a special ministry of primacy. Now that is exactly what the Second Vatican Council talked about in reaffirming the understanding of the local church. The trend since the Middle Ages was to see the church as one monolithic unity organized so that dioceses and parishes were lower divisions of the one church. The council reestablished the ancient view of local churches in communion. Bishops were once again understood to govern their dioceses in their own names as part of a college of bishops enjoying unity with each other and with the bishop of Rome. Now, after many years, this doctrine of the local church is fraught with much tension and not yet fully accepted. Since the time of the dissolution of the Roman empire, the Roman church has tended to respond to any centrifugal forces by stressing the need for unity through centralization. The Roman Curia has demonstrated a paternalistic attitude, attempting to protect other churches from harming themselves through error. The grassroots voices that ask for a hearing and sometimes for change are dismissed with the statement that the church is not a democracy. What is not faced is that the church is not imperialistic Rome, or feudal Europe, or a Byzantine court, or a medieval monarchy either. But the church has been, and sometimes still is, all of these. The church must be incarnated in human forms. The Celtic church is an intriguing example of another way it once was so incarnated. Could it not offer an alternative as a local church to a bureaucratic, power-based church today?

Though the Celtic culture may not have been the expression of a unified people, I nevertheless am immediately struck by its high degree of sophistication in art, technology, story, warfare, social mores, and religion. The recent archaeological finds have added to the wealth of what is known as "La Tène Art." Full of swirls, circles, and geometric figures, it is a form of abstract art unique for the time, especially in the West. These designs are playful, with a sense of the unending and eternal, showing some relation to or influence from the East. Visually, the Celts liked color, brightness, movement, and human and animal shapes in abstract forms. I believe we are in touch with the Celtic mind and imagination with this characteristic of the "spiral knot." Their mind and their imagination differed from our modern scientific and literal way of seeing things. Theirs was more of a "symbolic consciousness" that reveled in images, symbols, myths. They saw reality from the lens of eternity, with no beginning or end, no distinction of the seen and unseen. The circle, rather than the straight line, emerges as the figure that expresses so much of Celtic life. The importance of relationships and kinship; all persons in the clan being on the same plane rather than in hierarchical positions; the equality of men and women, of king and peasant - such are characteristics of Celtic life that reflect this way of seeing reality.

A "natural" propensity of the Celts for Christianity was their way of looking at the world and all reality. I have focused on their openness to the other world in the immediate material world around them, their seeing the sacred in the ordinariness of creation. I have also described what I called their "symbolic consciousness," an ability to see more than what is immediately visible. I believe this was a natural opening to the sacramental worldview that Christianity proclaimed. God could be touched, felt, tasted in bread, wine, and oil, and in human word and touch as well. How natural indeed! Isn't this what we present-day Christians have been trying to revive since the Second Vatican Council? The centuries leading up to that council had seen a "spiritualizing" of the sacraments and of creation in general. Theology stressed the philosophical "substance and accidents" of sacraments, their validity and liceity. Bread no longer looked or tasted like bread but was etherealized into an air-like wafer. The cup and wine disappeared despite the fact that Christ told us to celebrate Eucharist in that mode. A few drops of water sufficed at baptism, a smudge of oil for anointing. Were we afraid of matter? Was there a relationship here to our shame about the body, and even a downplaying of marriage? And doesn't the Celtic perspective seem much healthier as well as much more theologically correct for us today?

Monastic "beehive" cells on Skellig Michael