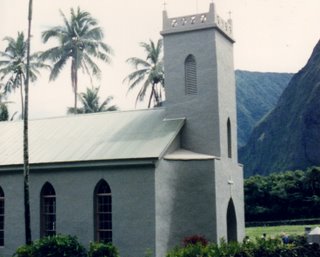

The view from St. Philomena Catholic Church in Kalawao, Molokai.

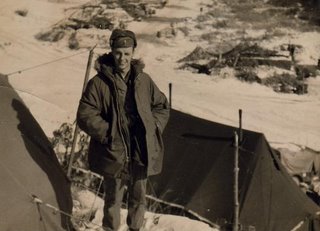

The view from St. Philomena Catholic Church in Kalawao, Molokai.When I was younger I was very fortunate to have had the opportunity to do some traveling. Several years ago my brother and I decided to take a trip together. We went with a tour group on a hiking vacation through the Hawaiian Islands. Backpacking every day and sleeping in tents, we went on excursions through Kauai, Molokai, Maui, and Hawaii (the “Big Island”). The weather on Hawaii is temperate and the tides don’t move very far in either direction.

After just a couple of nights I got tired of the tent and just took my sleeping bag and my tarp down to the beach so I could sleep out there. There are no pesky insects, the ocean crabs that come up on the beach at night don’t bite, and with the millions of stars overhead and the lulling, steady sound of the pounding surf, it was just amazing. After several days of roughing it, however, and “bathing” in the ocean or waterfall-fed pools, it felt really, really nice to get back under crisp-clean sheets again when we stayed for one night in a hotel in Lahaina. Sitting with my feet up on the courtyard veranda with a beer (I hardly ever drink) and listening to a hokey “Don Ho” type of Hawaiian band, it was one of the most pleasant evenings I think I ever spent.

In visiting most of the islands in the Hawaiian chain, I was struck by how different they all are. For me, Maui has just the right mix of civilized amenities and wild natural marvels. It was the only one of the islands I felt that I could actually stand to live on. My favorite island, though, was Molokai. It has an unspoiled feel to it, and it was the only place where I felt we had a chance to see how real native Hawaiians actually live. Hanging with some of them down by the beach, I developed an appreciation for the African reggae artist Alpha Blondy, who was very popular with the locals there at the time (click to hear Realplayer sample of Apartheid Is Nazism).

For all of this reverie about an island paradise, Molokai was once the scene of a hellish place, and there is a faith story buried here. On the long flights over to Hawaii from Boston, I spent the time by reading the biography of Father Damien De Veuster, Damien the Leper, written by John Farrow (the father of actress Mia Farrow). I was very much looking forward to visiting the site of the leper colony on Molokai where Father Damien had lived and worked.

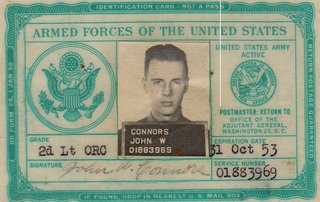

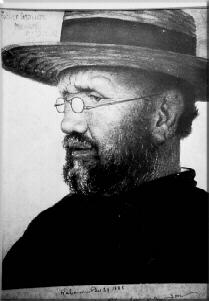

Father Damien, the son of Belgian farmers, was born as Joseph de Veuster in Tremeloo on January 3, 1840. The seventh of eight children, he decided to follow his older brother August into the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary (Picpus Fathers) . He took the name Brother Damien. August was slated to work the missions in Hawaii, but came down with typhus, and Damien begged his superiors to go in his brother's place. Permission was granted, and Brother Damien spent nine years on the big island, where he was ordained. After that period of time, he was sent to Molokai in 1873 to work at the leper colony on the Kalaupapa peninsula on what was supposed to be a rotational basis in the local bishop's plan. When he arrived and saw the appalling conditions there, Father Damien impressed upon the bishop the need for a full-time priest. He spent the rest of his life at the colony in Kalawao, until his death (of leprosy) in 1889.

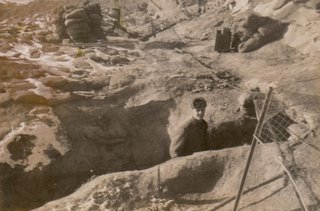

Looking down from the Topside Molokai cliffs above the leprosy hospital and settlement on the Kalaupapa peninusla.

The leper colony on Molokai had been in existence for some time before Father Damien had arrived. The Kalaupapa peninusla is remote and surrounded by a palisade of steep cliffs. Even today, it is inaccessible by land except by foot or sure-footed donkeys. It was thought that leprosy (commonly called Hansen's Disease today) came to the the vulnerable population of Hawaii via trading ships that had visited Chinese ports. The Hawaiian government had very litle means to deal with the victims of the disease. They were basically hauled onto boats and taken to Kalaupapa and dumped into the surf, left to fend for themselves in a lawless, squalid, Dante-esque settlement where the dead weren't even properly buried. For all intents and purposes, they were just left there to die, just as long as they were away from everyone else.

Father Damien was from peasant stock and brought solid carpentry skills with him to Hawaii. He was a man of immense physical strength and indefatigable energy. He slept outside under a tree at first, as there was little else there besides jerry-built shacks, and he tried as best as he could to avoid contagion. The first thing he did was to go about building a cemetery, so that the people there could start to build up at least the faintest beginings of a sense of self-worth and dignity as human beings. He rebuilt and expanded St. Philomena Church, and set about building homes for the people. He dug ditches and laid pipes for running water... He built just about everything that was ever built there with his own hands.

While he was a man of great personal warmth, he was also known for being somewhat brusque and didn't suffer fools well. He could become quite impatient over bureaucratic inefficiency and sloth. He was always championing the cause of the people in his care. This gave some the impression that he was a self-promoter, and caused some friction with his own superiors, the Hawaiian government, and missionaries from other faith traditions. This, more than anything else, is probably the reason why he has not been canonized yet.

Eventually of course, Father Damien contracted leprosy himself. In the everyday business of looking after his flock, he attended to them, nursed them, ate with them, dipped his hand into the same poi bowl with them, washed them, and buried them. He did all this out of his great love for them.

One morning he was pouring some hot water into a cup when the water swirled out and fell onto his bare foot. It took him a moment to realize that he had not felt any sensation. Gripped by the sudden fear of what this could mean, he poured more hot water on the same spot. No feeling whatsoever. Father Damien immediately realized what had happened. He had contacted the disease…

At the next Mass…

Damien: Fellow lepers…

(The people gasp. Father Damien has never started a homily this way. They are fellow lepers! He has leprosy. Some begin to cry.)

Congregation: No! No!

Damien: Yes, my friends, we are now lepers together. We will help one another. Together we lepers will praise and serve the Lord!

One thing that I found interesting in reading about Father Damien was the sexual stigma that people put around leprosy back then, and so by extension, to him. I'm sure that it was the same in Jesus' day, and that they did it to him as well. It still happens...

I thought this was a very good essay here about the life and mission of Father Damien, and here are some excerpts:

At the outset of his mission Damien aimed to restore in each leper a sense of personal worth and dignity. To show his poor battered flock the value of their lives, he had to demonstrate to them the value of their deaths. And so he turned his attention first to the cemetery area beside his little chapel. He fenced it around to protect the graves from the pigs, dogs, and other scavengers. He constructed coffins and dug graves. He organized the lepers into the Christian Burial Association to provide decent burial for each deceased. The organization arranged for the requiem Mass, the proper funeral ceremonies, and sponsored a musical group that played during the funeral procession.

He encouraged lepers to help him in all his activities. With their assistance he built everything from coffins to cottages. He constructed the rectory, built a home for the lepers’ children. When the colony expanded along the peninsula to Kalaupapa, he hustled the lepers into construction of a good road between Kalawao and Kalaupapa. Under his direction, lepers blasted rocks at the Kalaupapa shoreline and opened a decent docking facility. Damien taught his people to farm, to raise animals, to play musical instruments, to sing. He watched with pride as the leper bands he organized marched up and down playing the music Hawaiians love so well. No self-pity in this colony. Damien’s cheerful disposition and desire to serve touched the lepers’ hearts without patronizing or bullying them. Little by little their accomplishments restored the sense of dignity their illness threatened to destroy.

Under Damien’s vigorous lead, a sense of dignity and joy - and order - replaced Molokai’s despair and lawlessness. Neat, painted cottages, many of which the priest himself constructed, replaced the colony’s miserable shacks.

He harried the government authorities. In their eyes he was "obstinate, headstrong, brusque and officious." Joseph Dutton later on speaks of him as "vehement and excitable in regard to matters that did not seem to him right, and he sometimes said and did things that he afterwards regretted..., but he had a true desire to do right, to bring about what he thought was best. No doubt he erred sometimes in judgement.... In certain periods he got along smoothly with everyone, and at times he was urgent for improvements. In some cases he made for confusion, as various government authorities would not agree with him."

In all things his lepers came first. It would be a mistake, however, to think of Damien as a single-minded fanatic. He was a human being who was quick to smile, of pleasant disposition, of open and frank countenance...

...His superiors further accused Damien of being a "loner" because of his unhappy relationship with the three assistants they had sent him at different times. In all fairness, it probably is true that no one else could have lived with any of the three priests. But no one was more irritated by Damien’s fame than Hawaii’s Yankee missionaries.

Stern Puritan divines felt leprosy was the inevitable result of the Hawaiian people’s licentiousness. In their puritanical judgement the Hawaiian people were corrupt and debased. The segregation policy would have to be enforced to hasten the inevitable physical and moral collapse of the essentially rotten Hawaiian culture. There were medical doctors who were so convinced of an essential connection between leprosy and sexual immorality that they insisted that leprosy could be spread only through sexual contact.

When Damien entered his prison at Molokai, he had to make a decision. He believed that the Hawaiians were basically good and not essentially corrupt. And now he had to show them belief, regardless of the price. Thus, somewhere during the first part of his stay he made the dread decision to set aside his fear of contagion. He touched his lepers, he embraced them, he dined with them, he cleaned and bandaged their wounds and sores. He placed the host upon their battered mouths. He put his thumb on their forehead when he anointed them with the holy oil. All these actions involved touch. Touch is, of course, necessary if one is to communicate love and concern. The Hawaiians instinctively knew this. And that is why the Hawaiians shrank from the Yankee divines. Although these Yankee religious leaders expended much money on their mission endeavors, few Hawaiians joined their churches. The islanders sensed the contempt in which the puritan minds held them.

Damien was not, as we have noted, blind to the Hawaiians’ very real faults. Many Hawaiians, by their irregular sexual habits, greatly contributed to the spread of leprosy. But Damien knew that was not the only way the disease was communicated. Above all, he rejected the insufferable notion that God had laid this disease as a curse upon these people, to wipe them off the face of the earth. Damien hated leprosy. He didn’t see it as a tool of a vengeful God. He saw it as a suffering that man must eliminate. God loved the leper. No man had the right to scorn him.

Damien embraced the leper but not leprosy. He lived in great dread of the disease. When he first experienced leprosy’s symptomatic itching, while still a missionary at Kohala, some years before he went to Molokai, he knew then that the loathing diseased threatened him. Even when the disease had run a good bit of its brutal course through his body, he still at times seemed to refuse to admit he was a victim. But leprosy finally claimed him. It was the final price God exacted from Damien to show his sense of community and oneness with his poor afflicted flock.

Some said there was a connection between leprosy and venereal disease. In order to witness against those who claimed leprosy could only be spread by sexual contact, Damien submitted to the indignity of having his blood and body examined in detail after he had contracted the disease. Doctor Arning, a world-famous specialist in the disease, reported, after examination, that Damien had no sign of syphilis. In a signed statement dictated to Brother Joseph Dutton, his co-worker, Damien wrote, "I have never had sexual intercourse with anyone whomsoever."

History has borne out the wisdom of Damien’s decision to take these embarrassing measures. Shortly after Damien’s death, a Yankee divine of Honolulu, Doctor Charles McEwen Hyde, bitterly attacked the priest’s moral life. The good clergyman opined that Damien got leprosy because he was licentious.

Father Damien was not lacking defenders. In a magnificent statement, Robert Louis Stevenson, who had visited Molokai after Damien’s death, rose to champion the priest’s cause. The author’s defense of Damien rested upon the complete sacrifice the man made of his life, a sacrifice no Yankee missionary in Hawaii had duplicated.

...very early in his apostolate at Molokai, Damien was impelled to identify himself as closely as possible with his lepers. Long before he had the disease, he spoke of himself and the people of Molokai as "we lepers." Six months after his arrival at Kalawao he wrote his brother in Europe: "...I make myself a leper with the lepers to gain all to Jesus Christ. That is why, in preaching, I say ‘we lepers’; not, ‘my brethren....’"

Father Damien was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1995.

The Franciscan Sisters of Syracuse still tend to a handful of leprosy patients on Molokai. Shown below are some more of the photos I took in Kalawao. We had a Hawaiian patient drive us around the site in a bus. You would hardly notice that he had the disease, it is much more manageable today.

Just a sidenote to the story... I noticed quite a few mongoose running about the site. The bus driver explained that rats had arrived with the European ships, and some bright boy had the idea of bringing mongoose in to eradicate the rats. The problem is, one comes out at night, and the other during the day. So much for best laid plans and intentions!

Learn more about Leprosy (Hansen's Disease) today: The Leprosy Mission International

On a lighter note...

Going Native...

There's a contest going on at work over photos of the most adventourous moments on vacations. I was considering these entries from Molokai...

Going up the tree was a lot easier than coming down! :-O