Major General Wayne C. Smith of the US 7th Infantry Division decorates my father with the Silver Star for Bravery in Action - April, 1953

They say that the demilitarized zone between North Korea and South Korea is the “scariest place on earth”. I believe it. North Korea, of course, has been in the news lately for their recent nuclear weapons test. Every time Korea is in the news, it reminds me of my father, who was a Korean War veteran. My father passed away at the young age of 49. I was only 18 at the time. One of the things that saddens me the most is that I never really had the chance to have an adult conversation with him. One of the things that I regret the most is that I don’t feel I impressed upon him enough how much I loved him. Sometimes I dream that I’m having short conversations with my father; conversations that I’d give almost anything to have in reality.

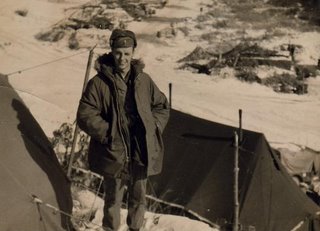

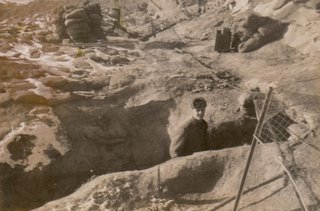

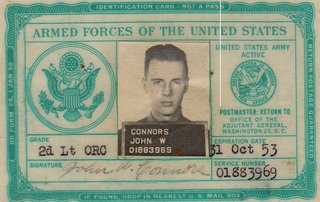

My father served in Korea during the last year of the war. He was an army artillery officer, a Second Lieutenant. He didn’t spend all of his time, however, studying maps and calling out orders from behind the howitzers. He did a lot of his work in “no man’s land” as a Forward Observer (FO). For those who don’t know what an FO does, his mission is basically to creep up as close as he can to the enemy lines and call down artillery strikes upon their positions, nearly on top of himself. It is one of the most dangerous jobs there is in the military.

He fought in the ferocious Battle of Pork Chop Hill, the last major engagement between the opposing forces before the truce was signed, and he was awarded the Silver Star for gallantry in action in connection with another incident (see the citation further down below).

The Korean War is often called America’s “forgotten war”, a stalemate sandwiched in between WWII and Viet Nam, but it was an exceedingly brutal war, with over 47,000 US soldiers killed in three years of combat. The number of North Korean and Chinese soldiers killed was over a million, and the combined number of South Korean soldiers and Korean civilians killed was probably more than double that. After the first year, which saw the opposing armies moving in a wild see-saw action down and up and down the peninsula, the last two years were largely a static affair, with the armies dug in across the width of the country. In that respect it resembled the trench warfare of WWI more than the mobile warfare of WWII.

The war also had an eerie, spectral, spooky quality to it, particularly after the Communist Chinese entered the conflict. The road-bound, mechanized units of the UN forces were in constantly in fear of being encircled by hordes of hardy peasant soldiers who seemed to be able to cover snow-bound mountain passes overnight on foot or on Mongolian ponies.

Much of the fighting was done at night, with the freezing, snow-covered hills illuminated by flares as the Chinese attacked the entrenched UN troops in human waves to the sound of bugles, whistles and gongs. The fighting was brutal and hand-to-hand, often coming down to individual fights with close range weapons like burp guns, hand grenades, and even bayonets.

Here is the description of the action for which my father was awarded the Silver Star.

HEADQUARTERS

7th INFANTRY DIVISION

APO 7

29 April 1953

GENERAL ORDERS

NUMBER 187

Section I

AWARD OF THE SILVER STAR.--By direction of the President, under the provisions of the Act of Congress, approved 9 July 1918 (WD Bu1. 43, I918), and pursuant to authority in AR 600-45, the Silver Star for gallantry in action is awarded to the following-named officer and enlisted man:

Second Lieutenant JOHN W. CONNORS, 02265280, Artillery, United States Army, a member of Battery C, 49th Field Artillery Battalion, distinguished himself by gallantry in action near Songhyon, Korea. On 5 March 1953, Lieutenant Connors, as a forward observer, accompanied an infantry combat patrol when the friendly patrol was suddenly ambushed by the enemy. As the ambush commenced, Lieutenant Connors fearlessly rushed from the support element to the front and delivered deadly and accurate fire upon the enemy forces. Without hesitation, Lieutenant Connors moved through the impact area to a vantage point completely exposed to the enemy fire and proceeded to rake the right flank with devastating protective fire, thus stopping the enemy. During the heavy bombardment of enemy mortar fire, Lieutenant Connors organized litter teams to evacuate the wounded and led them back to the friendly Main Line Of Resistance.

The gallantry displayed by Lieutenant Connors reflects great credit on himself and is in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service. Entered the Federal service from Massachusetts.

At this point in my life, I am exploring the possibilities of Christian pacifism…. but I have to say that growing up, we were always extremely proud of our father’s service, and for the honor that he had won. In fact, I am still proud of him. I cannot imagine myself at his age (or any age) having the guts to do such a thing. I just can’t see myself in that situation at all, other than curled up in a ball in the fetal position. As proud as we were, however, it never really occurred to us to deeply ponder what his own memory of the incident was like. As clear as it was that he saved the lives of many of his fellow soldiers, he also killed people. As far as I can tell from what the incident sounded like, he killed lots of people. How did this sit on his mind? What affect did this have on him over the ensuing years? If there were times when my father like to spend time alone in the basement on weekends, and to have a few drinks, perhaps we could have cut him a little more slack, or at least made an attempt to be more solicitous and understanding.

It’s difficult for me to get an accurate read. When I was a kid, he would never talk about the war with us. I’d ask him what he did in the war, and his terse, self deprecating reply would be “I hid” (I suppose there was a bit of truth in that, considering his role as an FO). He was consciously careful never to glamorize any of this stuff for us. He didn’t allow us to watch TV shows like ‘Combat’ and Garrison’s Guerrillas” that dramatized war in Hollywood fashion for popular entertainment. The sitcom “Hogan’s Heroes” would make him furious... If he ever caught us watching that, it wasn’t pleasant. “What, do you think living in a POW camp was a funny? Do you think it was some kind of joke?”. On the other hand, he rarely ever missed an episode of * Mash *, because it was in Korea, and I suspect, because the attitude of the characters was one of cynicism and skepticism regarding the war. He was a staunch Democrat, opposed to the war in Viet Nam and openly contemptuous of Richard Nixon.

Since my father passed away so young, it has been left for me to try to glean an opinion from the impressions of others. According to my mother (who also passed away quite young), my father had a certain gentleness and sweetness to him that was gone when he came back from Korea. He’d adopted the stern, no-nonsense demeanor of an officer. In her conversations with him, he’d related that he was struck by the wastefulness of war in its wanton destruction of young lives. In one telling anecdote, she mentioned his sorrow and revulsion at dispatching enemy soldiers by bayonet, saying to them and to himself - “I have nothing against you.”

According to my aunt, the impression he left was how much he hated the bitter winter cold of Korea, and how much he wanted to come home if for no other reason than to get warm.

A couple of years ago, I was relating these conversations to my uncle, my father’s younger brother. He listened all the way through politely with a wry smile on his face. Then he said to me, “Your father loved it. He was a good soldier and he never felt more alive than when he was doing a soldier’s job. There was a certain colonel who had it in for him for what he perceived as his insubordination. This colonel thought he was punishing my father for making him serve as an FO, but my father thrived on it, because he liked doing that kind of mission. He enjoyed the danger and the excitement.”

What to believe? Was that an older brother’s bravado to a competitive younger brother? An unwillingness not to discuss a soft side that he’d be willing to reveal to a wife? Is it possible that both sides of the story are true? I think the issue is complicated. He’d probably say that he’d consider all of this concern of mine to be to be soft. To be crap.

I don’t know if combat had any affect on my father, but it is hard for me to imagine that it had none whatsoever. In more extreme cases, the affects of stress under fire are well-known. In WWI, they would call is Shell shock. In WWI they would call it Battle Fatigue. After Viet Nam, they would call it PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). What about the Korean vets?

During America’s forgotten war, the WWII vets would say to the returning troops, “We plastered the Japs and the Krauts. What’s going wrong in Korea? What the hell is wrong with our army over there?” Many of their sacrifices were unappreciated. Have their traumas been unappreciated as well?

12 comments:

Jeff, Peace! It was good and hard for me to read your reflection on Korea. My dad and several uncles served there. One uncle won a silver star. Another was at Pork Chop Hill and my dad said it affected him all his life. I can believe that the experience perhaps both hardened and enlivened your dad. Human beings are interesting that way. But in one way, I think that's one of the horrors of war: that it can make people not only kill others, but get some rush out of it. Anyway, thanks again for the reflection. God bless and keep you!

Interesting, Jeff. Thanks for sharing this.

My father was in Korea too, though I don't know much about what happened to him there - just that he was the only one in his group that wasn't killed and that it changed him for the worse.

I know what it's like too to try to learn more about one's father from others. My mother would never talk about him except to say bad things, then once an older cousin told me she had visited us when I was about three, just before my parents broke up, and that my father had just painted a mural on the wall of my bedroom and that he loved me.

Your father sounded like a complex person - brave, intelligent, vulnerable, and thoughtful.

Hi Rashfriar,

Your father and uncles served there too? Were they in the 7th Infantry Division as well, out of Massachusetts?

I think that you're right. I think it's possible that there can be a bit of duality there, both in the experience and as a result of it...

Thanks Crystal,

I remember that you once said that your father's service in Korea was very hard on him. I'm very sorry about that. I'm glad that your cousin offered a positive reflection on him. I think the best thing that separated parents can do is try to keep their children from holding resentments towards the other. I'm of the opinion that one should try to say the best things one can, but sometimes circumstances make that impossible.

Jeff,

Once again a great post. I think you could be a very good memoir-writer.

One horrible though less obvious consequence of war is that even the soldiers who make it home alive and intact return after seeing and doing truly terrible things. I imagine that the extremity of the situation can bring out the best in people, but there is also the danger of bringing out the worst. When I read about the worst excesses committed by the US troops in Iraq, one of my reactions is of great bitterness that very, very young Americans who should be home watching football games on TV and mowning the lawn have been turned into monsters.

Wonderful post Jeff. During all these years of our friendship you have been very quiet (private) about your Dad. He sounds like an extraordinary man and I can't help but recognize a lot of my best friend Jeff Connors in there. I agree with Crystal about the complexity that was evidently a part of his character. In fact, its probably a reflection of how we humans are in general, but pulled forward to the surface in a more apparent way by virtue of such a horrific yet somehow "energizing" experience. At that moment clearly its kill or be killed and your father's overwhelming gut reaction was clearly the former. By the time young, brave men find themselves in those situations - (including the young Korean men who he had nothing against) - it too late. The damage is done. We've put them way beyond the point of no return...its instinct at work. But I can't help asking myself why we still endorse putting these young men and women into these irreversible and devastating situations. As long as they are "charged" with nobel causes for which to fight, they will continue to deliver themselves with amazing bravery and committment. As you know, my dad volunteered and fought in WWII in the Italian theatre. Though in later years he has been prone to talk (a lot) about a few of the relatively unimportant things that happened there, for most of his life he has kept the REAL experience deep inside and I believe it had a profoundly negative impact on his vision of the world/society he has lived in ever since. The older I get and the more nobel wars I see come and go, the more I'm convinced sadly that things (and causes) are rarely what they are cracked up to be.

The current war in Iraq recently was the subject of an article in The Lancet. (After nearly 20 years working in healthcare I know that The Lancet, together with the New England Journal of Medicine, are among the most scientifically demanding publications in the world. It is exceedingly difficult to publish in them because of the high demands placed on the scientific rigour of any studies that appear in them.) It could be that for this particular article they suddently lowered all of their standards for scientific rigour behind the studies' data, but I find it highly unikely. The study cited an estimated 650,000 civilians killed in the Iraq war so far. The figure was quickly written off (by President Bush) as being unrealistic. I fear its probably not so far off, but it would be inconvenient for us to know, so we won't (in fact there is very little official military information on this because it is considered too difficult to estimate.) I write all this because I think we can avoid putting the John Connors' of this world into these situations. In fact, men like your dad and mine (and the guys in Iraq today) who are willing to sacrifice so much on behalf of others - because that is what they were convinced they were doing - are amazingly valueable assets to humanity and I can't help but believe there are better ways to harness their strengths. As the horrendously high number of civilian casualties always attest, thrown into the soup with these brave soldiers are civilians (women and children) who go literally unaccounted for. It all has me thinking (almost non-stop): Even under the most defensable, justifiable circumstances can we allow ourselves to go on warring? Worse still, the real causes behind the causes remain increasingly doubtful for me. The example of your dad Jeff tells me again that the Spirit that lies within deserves better.

Thanks for sharing this post with us Jeff.

PEACE!

Joe

ps there's an interesting video in Google Videos called Robert Newman's History of Oil. I'm afraid I am one of the several billion persons on earth not familiar with all of the (true) historical facts that lead to the wars of the last century. So, I can't defend his history lesson...its certainly well done and deserves a look.

Thanks Liam,

It makes you wonder if such a thing as a just war is even possible. War brutalizes almost everyone it touches so thoroughly, that it is very hard to come out of it cleanly, especially in a counter-insurgency conflict like the one in Iraq. This government asks quite a lot of idealistic young men and women by putting them in these impossible circumstances, and there isn't enough concern for their mental health when they return. Quite often they find that they miss being back with their units, as hellish as the experience may have been. They feel like their brothers "over there" are the only ones who can really understand them anymore. It can bring out the worst in people, but it can bring out the very best in some of them too. There are Hadithas and Abu Ghraibs, but also I believe that there are many who take their profession seriously who are working very hard over there, doing the best that they can for the Iraqi people and what they sincerely believe in, and they often put their own lives at extra risk in an effort not to harm innocents. It's sad to see such concern and professionalism wasted on such a misguided effort.

Hi Joe,

Good comments... Very busy right now. I'll reply at length when I get a chance. I'll also check out that Newman video...

Hi Joe,

Yeah, I've always been quite private, at least as far as family matters are concerned. Not sure what it is inside me that compels me to want to write about certain things nowadays. Maybe it's because my brother and I are the last ones left. Regarding the Songhyon incident, the way my father put it to my uncle, he said "I just lost it", but that explanation isn't deep enough. It's too facile. I think we know a bit about this too from your own dad. The more these guys saw the less they wanted to talk about it when they were young. They just came home and got on with things. Look at your dad - Army Air Corps in WWII. The way he told it, he'd have you believe that he spent all of his time in the motor pool although we know he came back with a broken back and a dresser drawer full of medals. Late in life is when he started to talk about these things and started getting matters off his chest...

You talk about the number of people killed in Iraq as reported in that study. The number I usually hear is that 100 people are killed per day in Iraq directly by violence, and over a three year period, if the number of people who die indirectly through stress, heart attacks, ilnness, etc... are taken into account, perhaps those numbers aren't that unrealistic.

I think the older we get, the more we see people and nations fall into the same pattern of mistakes as earlier generations, and you get more cynical about hearing one rational after another when it's all been said before. There will always be another war to fight, it seems. I'll have to study up on this oil business. It's getting harder and harder for me to believe that there is nothing to it. Look at how the skyrocketing cost of oil plummeted in the last few months in advance of this November's elections. It can't help but to feed a bit of cynicsim in me.

Jeff,

this is off the subject, but remember when you told me about the resurrection beliefs of Jesus' time? There's an intersting post by Alan F. Segal at the Busybody on resurrection and the afterlife that you might like.

Thanks Crys,

Alan Segal is a good scholar. I was reading his book 'Life After Death' around the time I started the blog. I'll give this article a read, thx.

I'm fortunate to be sitting here with my 87 yr old father who was in 7th div, 17th inf Reg, L Co in '53. He arrived as a replacement during one of the Major Chinese pushes to take pork Chop. After a few months in the trenches along a ridge, he was assigned to the motor pool and drove the 2.5 ton truck non stop - day, night, mud, snow etc. yes, they did suffer PTSD. Dad still has occasional night terrors and other. Issues we think are related to the experience. He's never seen anyone for it. Your dad had a critical role. Massive volumes of artillery placed on target is the only thing that kept the Chinese in check.

Thanks for the post, Vicksburg. I am sorry I did not see it until now. Please thank your father for his service on my behalf. I hope he is doing well.

Post a Comment