It's Friday, and it's Spring

Too much emphasis on dark material lately? I find that it's hard to listen to this tune and not smile.

Bob Marley - Three Little Birds

Our youngest daughter just turned five. It's kind of a strange feeling. It's been a long, long time since we've had no really little kids in the house, and it will be this way from now on....

She likes to sing this song with me when we brush our teeth and get her washed and dressed for bed. I can tell she's getting older because she likes to make up her own goofy lyrics for it now. This is something all my kids like to do. They all like to riff on songs with their own satirical lyrics. I wonder why that is? They even do it with Christmas carols. It drives me crazy sometimes, how they all like to grab the spotlight and imagine themselves as stand-up comics at the dinner table, but hey, at least they're creative.

Enjoy and have a good weekend.

Bob, we barely knew ye.

Friday, March 28, 2008

Monday, March 24, 2008

Same Old, Same Old... As the 'Lost Generation' Passes On

Thoughts on 5 Years, 4,000 Dead, and the Last of the World War I Vets

Frank Buckles.

Frank Buckles.

As we passed the fifth anniversary of the start of the war in Iraq, and crossed the threshold of 4,000 US deaths in Iraq shortly afterwards, I also happened to notice that at the age of 107, Frank Buckles was recently honored for being the last surviving US veteran of the First World War.

It was also reported that the last surviving French World War I veteran passed away recently at the age of 110. Apparently, worldwide, there are just a handful of surviving veterans remaining from that conflict, billed at one time as "the War to End All Wars."

If we look at the rates of those killed in action in Iraq, it has been at the rate of about 3 per day, with spikes occurring around the battles in Fallujah and in certain phases of the surge. The last thing I would ever want to do is to minimize the suffering that has been endured by our wounded vets, the families of those who have lost loved ones, and of the innocent people of Iraq caught in the crossfire. As the last of the "Lost Generation" of World War I passes away from history, however, as terrible as the Iraq numbers are, I can't help but to be aghast at the comparative numbers lost in the muck and maw of that war nearly 100 years ago, a war that in many ways gave shape to the world and the enduring conflicts we see to this day.

A book I'm reading now called 14-18 presents statistics that are almost too horrible for the mind to grasp. With the exception of Russia, the average daily mortality rates for the major combatant nations were worse in WWI than they were in WWII. For Germany, it was 1,303 per day. For Great Britain, 457 per day. For the US, 195 per day, which spiked up to 820 per day by the time we became fully engaged in the Summer of 1918. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, on July 1, 1916, the British lost 20,000 men killed and 40,000 wounded.

Last year I posted about Erich Maria Remarque and the invention of the anti-war novel. I've been plowing through some of Remarque's novels dealing with the post-war period lately. His books really speak to me for some reason, but I've had to put then down for a while. They never end happily. In fact, the endings are invariably disturbing. It gets to be too much.

As I think about the Iraq War and the manipulation of certain data in the run-up to it, I'm reminded of the English poet Siegfried Sassoon, World War I veteran, and author of Memoirs of an Infantry Officer. Siegfried was an apt name for him. He was a courageous and ferocious soldier; an absolute terror to the Germans (something to bear in mind when considering the controversy over gays in the military). He was a highly decorated officer, but by 1917 he had had enough and renounced his commission, refusing to return to the front after recovering from wounds. In a public announcement in the Bradford Pioneer newspaper:

Second-Lieutenant Siegfried Sassoon,

Third Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers

“Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration”

(This statement was made to his commanding officer by Second-Lieutenant S. L. Sassoon, Military Cross, recommended for D.S.O., Third Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers, as explaining his grounds for refusing to serve further in the army. He enlisted on 3rd August 1914, showed distinguished valour in France, was badly wounded, and would have been kept on home service if he had stayed in the army.)

I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority, because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it.

I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that this war, upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of aggression and conquest. I believe that the purposes for which I and my fellow soldiers entered upon this war should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible to change them, and that, had this been done, the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation.

I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops, and I can no longer be a party to prolong these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust.

I am not protesting against the conduct of the war, but against the political errors and insecurities for which the fighting men are being sacrificed.

On behalf of those who are suffering now I make this protest against the deception which is being practiced on them; also I believe that I may help to destroy the callous complacence with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share, and which they have not sufficient imagination to realize.

July, 1917. S. Sassoon.

Same old, same old... Does anything ever really change?

His friend Robert Graves, fellow officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, and poet in his own right, noted in his book Goodbye To All That:

His friend Robert Graves, fellow officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, and poet in his own right, noted in his book Goodbye To All That:

England looked strange to us returned soldiers. We could not understand the war madness that ran about everywhere, looking for a pseudo-military outlet. The civilians talked a foreign language, and it was a newspaper language. I found serious conversation with my parents all but impossible. Quotation from a single typical document of this time will be enough to show what we were facing.

A Mother's Answer to 'A Common Soldier'

Going up against such steadfast jingoism, Graves testified at Sassoon's court-martial, doing the only thing that he could with any chance of success - Arguing in front of a medical board that Sassoon should be declared to have shell shock instead of being being court-martialed.

There are many way of course, that people deal with immense grief and sorrow. The "Little Mother's" is one familiar way. There are other ways as well. One especially pernicous aspect of World War I is that a huge percentage of the bodies of the fallen were never recovered. In Britain there was a huge upsurge in spiritualism, occult practices, and the holding of seances. Practitioners included such luminaries as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling, who both lost sons in combat. Graves told a story: Towards the end of September, I stayed in Kent with a recently wounded First Battalion friend. An elder brother had been killed in the Dardanelles, and their mother kept the bedroom exactly as he had left it, with the sheets aired, the linen always freshly laundered, flowers and cigarettes by the bedside. She went around with a vague, bright religious look on her face. The first night I spent there, my friend and I sat up talking about the War until after twelve o'clock. His mother had gone to bed early, after urging us not to get too tired. The talk had excited me, and though I managed to fall asleep an hour later, I was continually wakened by sudden rapping noises, which I tried to disregard but which grew louder and louder. They seemed to come from everywhere. Soon sleep left me and I lay in a cold sweat. At nearly three o'clock, I heard a diabolic yell and a succession of laughing, sobbing shrieks that sent me flying to the door. In the passage I collided with the mother who, to my surprise, was fully dressed. "It's nothing," she said. "One of the maids had hysterics. I'm so sorry you have been disturbed.” So I went back to bed, but could not sleep again, though the noises had stopped. In the morning I told my friend: “I'm leaving this place. It's worse than France.” There were thousands of mothers like her, getting in touch with their dead sons by various spiritualistic means.

There are many way of course, that people deal with immense grief and sorrow. The "Little Mother's" is one familiar way. There are other ways as well. One especially pernicous aspect of World War I is that a huge percentage of the bodies of the fallen were never recovered. In Britain there was a huge upsurge in spiritualism, occult practices, and the holding of seances. Practitioners included such luminaries as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling, who both lost sons in combat. Graves told a story: Towards the end of September, I stayed in Kent with a recently wounded First Battalion friend. An elder brother had been killed in the Dardanelles, and their mother kept the bedroom exactly as he had left it, with the sheets aired, the linen always freshly laundered, flowers and cigarettes by the bedside. She went around with a vague, bright religious look on her face. The first night I spent there, my friend and I sat up talking about the War until after twelve o'clock. His mother had gone to bed early, after urging us not to get too tired. The talk had excited me, and though I managed to fall asleep an hour later, I was continually wakened by sudden rapping noises, which I tried to disregard but which grew louder and louder. They seemed to come from everywhere. Soon sleep left me and I lay in a cold sweat. At nearly three o'clock, I heard a diabolic yell and a succession of laughing, sobbing shrieks that sent me flying to the door. In the passage I collided with the mother who, to my surprise, was fully dressed. "It's nothing," she said. "One of the maids had hysterics. I'm so sorry you have been disturbed.” So I went back to bed, but could not sleep again, though the noises had stopped. In the morning I told my friend: “I'm leaving this place. It's worse than France.” There were thousands of mothers like her, getting in touch with their dead sons by various spiritualistic means.

Frank Buckles.

Frank Buckles.As we passed the fifth anniversary of the start of the war in Iraq, and crossed the threshold of 4,000 US deaths in Iraq shortly afterwards, I also happened to notice that at the age of 107, Frank Buckles was recently honored for being the last surviving US veteran of the First World War.

It was also reported that the last surviving French World War I veteran passed away recently at the age of 110. Apparently, worldwide, there are just a handful of surviving veterans remaining from that conflict, billed at one time as "the War to End All Wars."

If we look at the rates of those killed in action in Iraq, it has been at the rate of about 3 per day, with spikes occurring around the battles in Fallujah and in certain phases of the surge. The last thing I would ever want to do is to minimize the suffering that has been endured by our wounded vets, the families of those who have lost loved ones, and of the innocent people of Iraq caught in the crossfire. As the last of the "Lost Generation" of World War I passes away from history, however, as terrible as the Iraq numbers are, I can't help but to be aghast at the comparative numbers lost in the muck and maw of that war nearly 100 years ago, a war that in many ways gave shape to the world and the enduring conflicts we see to this day.

A book I'm reading now called 14-18 presents statistics that are almost too horrible for the mind to grasp. With the exception of Russia, the average daily mortality rates for the major combatant nations were worse in WWI than they were in WWII. For Germany, it was 1,303 per day. For Great Britain, 457 per day. For the US, 195 per day, which spiked up to 820 per day by the time we became fully engaged in the Summer of 1918. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, on July 1, 1916, the British lost 20,000 men killed and 40,000 wounded.

Last year I posted about Erich Maria Remarque and the invention of the anti-war novel. I've been plowing through some of Remarque's novels dealing with the post-war period lately. His books really speak to me for some reason, but I've had to put then down for a while. They never end happily. In fact, the endings are invariably disturbing. It gets to be too much.

As I think about the Iraq War and the manipulation of certain data in the run-up to it, I'm reminded of the English poet Siegfried Sassoon, World War I veteran, and author of Memoirs of an Infantry Officer. Siegfried was an apt name for him. He was a courageous and ferocious soldier; an absolute terror to the Germans (something to bear in mind when considering the controversy over gays in the military). He was a highly decorated officer, but by 1917 he had had enough and renounced his commission, refusing to return to the front after recovering from wounds. In a public announcement in the Bradford Pioneer newspaper:

Second-Lieutenant Siegfried Sassoon,

Third Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers

“Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration”

(This statement was made to his commanding officer by Second-Lieutenant S. L. Sassoon, Military Cross, recommended for D.S.O., Third Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers, as explaining his grounds for refusing to serve further in the army. He enlisted on 3rd August 1914, showed distinguished valour in France, was badly wounded, and would have been kept on home service if he had stayed in the army.)

I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority, because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it.

I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that this war, upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of aggression and conquest. I believe that the purposes for which I and my fellow soldiers entered upon this war should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible to change them, and that, had this been done, the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation.

I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops, and I can no longer be a party to prolong these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust.

I am not protesting against the conduct of the war, but against the political errors and insecurities for which the fighting men are being sacrificed.

On behalf of those who are suffering now I make this protest against the deception which is being practiced on them; also I believe that I may help to destroy the callous complacence with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share, and which they have not sufficient imagination to realize.

July, 1917. S. Sassoon.

Same old, same old... Does anything ever really change?

His friend Robert Graves, fellow officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, and poet in his own right, noted in his book Goodbye To All That:

His friend Robert Graves, fellow officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, and poet in his own right, noted in his book Goodbye To All That: England looked strange to us returned soldiers. We could not understand the war madness that ran about everywhere, looking for a pseudo-military outlet. The civilians talked a foreign language, and it was a newspaper language. I found serious conversation with my parents all but impossible. Quotation from a single typical document of this time will be enough to show what we were facing.

A Mother's Answer to 'A Common Soldier'

Going up against such steadfast jingoism, Graves testified at Sassoon's court-martial, doing the only thing that he could with any chance of success - Arguing in front of a medical board that Sassoon should be declared to have shell shock instead of being being court-martialed.

There are many way of course, that people deal with immense grief and sorrow. The "Little Mother's" is one familiar way. There are other ways as well. One especially pernicous aspect of World War I is that a huge percentage of the bodies of the fallen were never recovered. In Britain there was a huge upsurge in spiritualism, occult practices, and the holding of seances. Practitioners included such luminaries as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling, who both lost sons in combat. Graves told a story: Towards the end of September, I stayed in Kent with a recently wounded First Battalion friend. An elder brother had been killed in the Dardanelles, and their mother kept the bedroom exactly as he had left it, with the sheets aired, the linen always freshly laundered, flowers and cigarettes by the bedside. She went around with a vague, bright religious look on her face. The first night I spent there, my friend and I sat up talking about the War until after twelve o'clock. His mother had gone to bed early, after urging us not to get too tired. The talk had excited me, and though I managed to fall asleep an hour later, I was continually wakened by sudden rapping noises, which I tried to disregard but which grew louder and louder. They seemed to come from everywhere. Soon sleep left me and I lay in a cold sweat. At nearly three o'clock, I heard a diabolic yell and a succession of laughing, sobbing shrieks that sent me flying to the door. In the passage I collided with the mother who, to my surprise, was fully dressed. "It's nothing," she said. "One of the maids had hysterics. I'm so sorry you have been disturbed.” So I went back to bed, but could not sleep again, though the noises had stopped. In the morning I told my friend: “I'm leaving this place. It's worse than France.” There were thousands of mothers like her, getting in touch with their dead sons by various spiritualistic means.

There are many way of course, that people deal with immense grief and sorrow. The "Little Mother's" is one familiar way. There are other ways as well. One especially pernicous aspect of World War I is that a huge percentage of the bodies of the fallen were never recovered. In Britain there was a huge upsurge in spiritualism, occult practices, and the holding of seances. Practitioners included such luminaries as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling, who both lost sons in combat. Graves told a story: Towards the end of September, I stayed in Kent with a recently wounded First Battalion friend. An elder brother had been killed in the Dardanelles, and their mother kept the bedroom exactly as he had left it, with the sheets aired, the linen always freshly laundered, flowers and cigarettes by the bedside. She went around with a vague, bright religious look on her face. The first night I spent there, my friend and I sat up talking about the War until after twelve o'clock. His mother had gone to bed early, after urging us not to get too tired. The talk had excited me, and though I managed to fall asleep an hour later, I was continually wakened by sudden rapping noises, which I tried to disregard but which grew louder and louder. They seemed to come from everywhere. Soon sleep left me and I lay in a cold sweat. At nearly three o'clock, I heard a diabolic yell and a succession of laughing, sobbing shrieks that sent me flying to the door. In the passage I collided with the mother who, to my surprise, was fully dressed. "It's nothing," she said. "One of the maids had hysterics. I'm so sorry you have been disturbed.” So I went back to bed, but could not sleep again, though the noises had stopped. In the morning I told my friend: “I'm leaving this place. It's worse than France.” There were thousands of mothers like her, getting in touch with their dead sons by various spiritualistic means.

Sunday, March 23, 2008

Easter 2008

Noli me tangere, by Correggio (c. 1522-1525)

Jesus put his trust in the Father, that he would not disappear and tumble into the darkness of death. He was raised up to eternal life, and in this we also put our hope.

If there is no resurrection of the dead, then neither has Christ been raised.

And if Christ has not been raised, then empty (too) is our preaching; empty, too, your faith.

Then we are also false witnesses to God, because we testified against God that he raised Christ, whom he did not raise if in fact the dead are not raised.

For if the dead are not raised, neither has Christ been raised,

and if Christ has not been raised, your faith is vain; you are still in your sins.

Then those who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished.

If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are the most pitiable people of all.

But now Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep.

And if Christ has not been raised, then empty (too) is our preaching; empty, too, your faith.

Then we are also false witnesses to God, because we testified against God that he raised Christ, whom he did not raise if in fact the dead are not raised.

For if the dead are not raised, neither has Christ been raised,

and if Christ has not been raised, your faith is vain; you are still in your sins.

Then those who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished.

If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are the most pitiable people of all.

But now Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep.

--1 Cor 13-20

Happy Easter, everyone.

Thursday, March 20, 2008

Triduum

Dead Christ Supported by Angels, by Giovanni Bellini (c. 1470)

Then he said to them,"My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death. Stay Here and Keep Watch With Me."

-- Matthew 26:38

http://www.hymnprint.net/download/GC2433_StayHereandKeepWatch.mp3

Music by Jacques Berthier

Wednesday, March 19, 2008

A.D. 33

Christ at the Column, by Caravaggio (1607)

GOOD FRIDAY, A.D. 33

Mother, why are people crowding now and staring?

Child, it is a malefactor goes to His doom,

To the high hill of Calvary He's faring,

And the people pressing and pushing to make room

Lest they miss the sight to come.

Oh, the poor malefactor, heavy is His load!

Now He falls beneath it and they goad Him on.

Sure the road to Calvary's a steep up-hill road --

Is there none to help Him with His Cross -- not one?

Must He bear it all alone?

Here is a country boy with business in the city,

Smelling of the cattle's breath and the sweet hay;

Now they bid him lift the Cross, so they have some pity:

Child, they fear the malefactor dies on the way

And robs them of their play.

Has He no friends then, no father nor mother,

None to wipe the sweat away nor pity His fate?

There's a woman weeping and there's none to soothe her:

Child, it is well the seducer expiate

His crimes that are so great.

Mother, did I dream He once bent above me,

This poor seducer with the thorn-crowned head,

His hands on my hair and His eyes seemed to love me?

Suffer little children to come to Me, He said --

His hair, his brows drip red.

Hurrying through Jerusalem on business or pleasure

People hardly pause to see Him go to His death

Whom they held five days ago more than a King's treasure,

Shouting Hosannas, flinging many a wreath

For this Jesus of Nazareth.

-- Katharine Tynan (1918)

Sunday, March 16, 2008

In a More Nurturing Time and Place...

Remembering Holy Week as it used to be...

Christ Entering Jerusalem, by Giotto (1304-1306)

From The Christian Century, John M. Buchanan's A Passion Narrative:

I'm not sure exactly when it happened, but at some point the liturgical calendar changed and Palm Sunday became Passion Sunday, with the strong suggestion that we read as much of the Passion narrative as we can on this Sunday before Easter. I always rather liked the older tradition of marking Passion Sunday two weeks before Easter as a time to devote attention to the Passion, Christ crucified, and then to deal with the powerful complexity of his entry into the capital city on the first day of Holy Week.

Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan discuss these liturgical changes and recall how Good Friday used to be celebrated. People my age remember: it was a school holiday and we spent three hours in church, from noon until 3, listening to seven preachers have at the "seven last words" of Christ. My memories of those hours are that it was a very long time to be confined to a pew on a spring afternoon, with the baseball diamond summoning. But it did impress me that something very significant was at the heart of it, something that warranted a lot of my attention. Borg and Crossan suggest that when Good Friday stopped being recognized as a public holiday, the story of the crucifixion was heard by fewer and fewer people. So "the story needs to be told on the Sunday before Easter." I can't argue with the logic of that, but I do lament and resist diluting the complex power of Palm Sunday.

In their book The Last Week, Borg and Crossan follow the Gospel of Mark's account of Jesus' last week, day by day, hour by hour. In the process they note details that we might overlook. They dispel the notion that the crowd that welcomed Jesus turned against him during the week. How many sermons have been preached on that theme? The crowd was his protection, it turns out. The authorities were afraid of the crowd. The crowd that gathered in Pilate's courtyard and demanded his crucifixion wasn't the Palm Sunday crowd at all, but "supporters of the authorities--perhaps a few dozen people." That is an important observation. And more than ever, it makes me want to be there on Palm Sunday, when the children sing sweet hosannas and tears come to grandparents' eyes.

I can relate very strongly to what Mr. Buchanan is saying here, about Holy Week, and Good Friday in particular. When I was a kid, back in the 60's, Holy Week was a very big deal, and each day had a different and special emphasis.

We always had the day off from school on Good Friday, but it was a day to be kept silently and solemnly. It was a lot like coming home after a funeral. Very serious business... One thing that lifted the tension a bit was the fact that the television stations would run nonstop religious programming, with hour after hour of continuous biblical epics. One of the ones I remember especially was The Robe. A slave named Demetrius (Victor Mature) is owned by a Roman Tribune named Marcellus (Richard Burton). Demetrius, who first notices Jesus upon his entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, becomes a follower and recovers the robe of Jesus at the site of the crucifixion, which took place under a Roman cohort led by Marcellus. To make a long story short, both Demetrius and Marcellus become converts, with Marcellus eventually martyred with his betrothed, Diana, under Caligula.

Victor Mature and Richard Burton in The Robe (1953)

It's a film that would certainly be considered hokey and corny by today's standards, but there are certain things I still like about it. For example, I like the fact that the face of Jesus is never shown in any of the scenes. That gives it added power somehow.

Yes, it might seem corny today, but for kids, this stuff was formative, and I'd say that it was mostly in a good way. None of this exists for kids anymore, unless their parents insist upon being completely counter-cultural. I feel fortunate in some respects to have been born in a time that preceded the Culture Wars, a time when faith was a given and there was no inherent hostility to be found as a matter of necessity between people of faith and people in the media. For all the faults of those years, and there were many, I think it was a more nurturing time for children overall.

Actually, as I listen to the screenplay again in these scenes, I'm struck at how radical they are, in terms of indicting Roman imperial aggression. It's almost as if John Dominic Crossan could have been an advisor. ;-D

Video clips:

Demetrius recovers the robe

Marcellus refuses to apostasize before Caligula

Watch 'em quick, before Youtube pulls them...

Christ Entering Jerusalem, by Giotto (1304-1306)

From The Christian Century, John M. Buchanan's A Passion Narrative:

I'm not sure exactly when it happened, but at some point the liturgical calendar changed and Palm Sunday became Passion Sunday, with the strong suggestion that we read as much of the Passion narrative as we can on this Sunday before Easter. I always rather liked the older tradition of marking Passion Sunday two weeks before Easter as a time to devote attention to the Passion, Christ crucified, and then to deal with the powerful complexity of his entry into the capital city on the first day of Holy Week.

Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan discuss these liturgical changes and recall how Good Friday used to be celebrated. People my age remember: it was a school holiday and we spent three hours in church, from noon until 3, listening to seven preachers have at the "seven last words" of Christ. My memories of those hours are that it was a very long time to be confined to a pew on a spring afternoon, with the baseball diamond summoning. But it did impress me that something very significant was at the heart of it, something that warranted a lot of my attention. Borg and Crossan suggest that when Good Friday stopped being recognized as a public holiday, the story of the crucifixion was heard by fewer and fewer people. So "the story needs to be told on the Sunday before Easter." I can't argue with the logic of that, but I do lament and resist diluting the complex power of Palm Sunday.

In their book The Last Week, Borg and Crossan follow the Gospel of Mark's account of Jesus' last week, day by day, hour by hour. In the process they note details that we might overlook. They dispel the notion that the crowd that welcomed Jesus turned against him during the week. How many sermons have been preached on that theme? The crowd was his protection, it turns out. The authorities were afraid of the crowd. The crowd that gathered in Pilate's courtyard and demanded his crucifixion wasn't the Palm Sunday crowd at all, but "supporters of the authorities--perhaps a few dozen people." That is an important observation. And more than ever, it makes me want to be there on Palm Sunday, when the children sing sweet hosannas and tears come to grandparents' eyes.

I can relate very strongly to what Mr. Buchanan is saying here, about Holy Week, and Good Friday in particular. When I was a kid, back in the 60's, Holy Week was a very big deal, and each day had a different and special emphasis.

We always had the day off from school on Good Friday, but it was a day to be kept silently and solemnly. It was a lot like coming home after a funeral. Very serious business... One thing that lifted the tension a bit was the fact that the television stations would run nonstop religious programming, with hour after hour of continuous biblical epics. One of the ones I remember especially was The Robe. A slave named Demetrius (Victor Mature) is owned by a Roman Tribune named Marcellus (Richard Burton). Demetrius, who first notices Jesus upon his entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, becomes a follower and recovers the robe of Jesus at the site of the crucifixion, which took place under a Roman cohort led by Marcellus. To make a long story short, both Demetrius and Marcellus become converts, with Marcellus eventually martyred with his betrothed, Diana, under Caligula.

Victor Mature and Richard Burton in The Robe (1953)

It's a film that would certainly be considered hokey and corny by today's standards, but there are certain things I still like about it. For example, I like the fact that the face of Jesus is never shown in any of the scenes. That gives it added power somehow.

Yes, it might seem corny today, but for kids, this stuff was formative, and I'd say that it was mostly in a good way. None of this exists for kids anymore, unless their parents insist upon being completely counter-cultural. I feel fortunate in some respects to have been born in a time that preceded the Culture Wars, a time when faith was a given and there was no inherent hostility to be found as a matter of necessity between people of faith and people in the media. For all the faults of those years, and there were many, I think it was a more nurturing time for children overall.

Actually, as I listen to the screenplay again in these scenes, I'm struck at how radical they are, in terms of indicting Roman imperial aggression. It's almost as if John Dominic Crossan could have been an advisor. ;-D

Video clips:

Demetrius recovers the robe

Marcellus refuses to apostasize before Caligula

Watch 'em quick, before Youtube pulls them...

Wednesday, March 12, 2008

Faith and the Making of the Republic

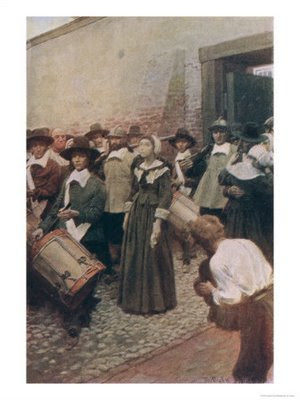

Mary Dyer on Her way to the Scaffold, by Howard Pyle (1906)

Mary Dyer, a Quaker, was hanged on Boston Common by Governor John Endicott in 1660.

I heard a pretty interesting program on NPR’s Fresh Air this week. Examining the Origins of America's 'Founding Faith' (39 minutes). It was an interview with Beliefnet editor Steven Waldman about his new book, Founding Faith: Providence, Politics, and the Birth of Religious Freedom in America. Waldman endeavors to debunk some myths about the “founding fathers” (and even seems to dispute that you can even say that there is such a group that can be accurately called that). Waldman claims that a set of diametrically-opposed myths have been built up around cherry-picked quotes selected by those who claim that the founding fathers wished to establish a Christian nation, and by those who claim that the founding fathers were simply Deists, Masons, and other types of skeptics who wanted to establish a decidedly secular state. According to Waldman, it’s more complicated than that, which is probably what most of us suspected anyway.

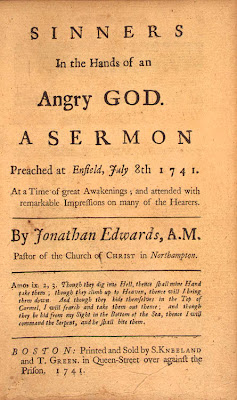

Jonathan Edwards,

Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God

Waldman somewhat disputes the notion that the original colonies were set up to establish “religious freedom”, pointing out that many, if not all of them, had strongly-established official ties between Church and State, as well as religiously-based criteria on who was allowed and not allowed to vote, etc… Many of these laws and official state religions persisted well after the Civil War. What Waldman does say about the original colonies was that they were, collectively, a Protestant redoubt. A fortress of the Reformation. It was as if each of the Protestant denominations at the time took a turn at trying to build the Kingdom of God, or Shining City on a Hill… About the only thing that they all had in common was a determination to be a bulwark against Popery and Romanism.

An image from the First Great Awakening.

George Whitefield was called "Dr. Squintum" by his critics...

Here are some links Beliefnet links about the book and the topic at hand.

Some interesting points to be heard in the NPR program and to read about on Beliefnet:

- The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment of the Constitution was initially understood to apply only at the Federal level. For many years afterwards, certain states still had their own established, official denominations. It wasn’t until after the Civil War and the passing of the Fourteenth Amendment that the Establishment Clause was understood to apply at the state level as well.

- George Washington, as evidenced in his speeches, believed that the success of the Revolution and the birth of the country was guided directly and only by the guiding hand of Divine Providence… He attended Anglican services, however, only about once a month, and did not take communion.

- Thomas Jefferson (unaware that the writing of St. Paul pre-dated the Gospels) was one of those who considered Paul the great corrupter of Christianity. A typical enlightenment thinker of his time, he denied the divinity of Jesus but considered his teachings to be sublime. He famously created his own cut-and-paste version of the Bible, excised of all that he considered supernatural humbug. Imagine a presidential candidate doing that today? Editing and cutting-and-pasting his own Bible? Nowadays, that's only done with policy and personal behavior.

- During the Revolutionary War, Washington, knowing that he had some Catholics in his ranks, and eager to enlist the help of Catholic France, was appalled by the Guy Fawkes Day celebrations of his troops, and banned further celebrations of it in the Continental Army.

- John Adams was a firm believer, and tried to jack Jefferson up a little bit, trying to make a Christian out of him. Jefferson let him know in the clearest terms just what he thought of Calvinism.

- The key man on the First Amendment was James Madison. He certainly couldn’t be described as a fundamentalist in his own beliefs, but he had many friends that he admired among the Baptists, and it was from them that he lit upon the idea and settled upon the conviction that Separation of Church and State was the principle that would be most conducive towards allowing religion in the United States to flourish. The free flourishing of religion was the goal.

Sunday, March 09, 2008

From the Good Samaritans to the Bad Samaritans

Disillusioned with the political process.... Do any of these candidates care about the most ordinary or the most vulnerable?

This epoch of globalization has become an era of media-driven insouciance - one allowing a journalist such as Thomas Friedman to retain his "expert" label while bragging that he "didn't even know what was in" a trade deal he championed. This is a time when the biggest economic deliberations are dominated by commentators berating Democrats for mentioning trade and then falling silent when Republicans praise pacts that eliminate jobs.

-- David Sirota (Hope in the time of NAFTA)

Much has been written about the case of Obama's economic guru, Austan Goolsbee, and the Canadians, but it's worth revisiting in the context of Monstergate. In telling the Canucks to pay no attention to his boss' saber-rattling on NAFTA, Goolsbee was being candid and stating the plain truth: Nobody who knows Obama believes for a second that he is anything but a staunch free trader; they know that he has no intention of trashing the trade treaty. But Goolsbee was also being sloppy. And so was the campaign in its ludicrously transparent, transparently ludicrous efforts to mislead the press about what occurred. (The Canadians contacted Goolsbee not in his capacity as Obama's guy on economics but merely as a University of Chicago academic? As Bill Clinton might put it, Give me a break!) The whole imbroglio fairly reeked of an operation that had become accustomed — too accustomed for its own good — to a sleepy, besotted press corps.

-- John Heilemann (Can Obama Handle the Awakened Media Beast?)

For those people who are consumed by the spectre of illegal immigrants making their way over the border from Mexico by the millions, and there appear to be a lot of such people worrying, it is important to note that "free trade" deals like NAFTA have not only been absolutely devastating to American workers, but to Mexican workers and farmers as well. NAFTA was a catastrophe for Mexico, and only served to exacerbate the problem we already had with illegal immigration. In the final Democratic presidential debate before the Ohio and Texas primaries, we saw Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama practically falling all over themselves trying to outdo each other in criticizing NAFTA and trying to disassociate themselves from it. Were either one of them being the least bit sincere about it at all? Was is sheer political opportunism and false populism on the part of both? Obama was a little late in coming to the anti-NAFTA table for my liking, and despite the Clinton administration's record on this, he wound up getting burned in particular when his University of Chicago economics adviser Austan Goolsbee visited the Canadian consulate in Chicago and basically gave the Canadians a wink and told them to cool it... telling them that Barack was just electioneering, and that he really didn't mean any of this stuff he was saying about wanting to renegotiate NAFTA (as if our problems with NAFTA , the WTO, and free trade deals had much to do with Canada anyway). The Obama campign handled the aftermath badly at first, trying to deny that Goolsbee had met with the Canadians, then trying to claim that he had been taken out of context. Really? Says Obama, "It was truthful based on what we knew at the time. Frankly, none of us were aware that Austan had gone to the Canadian consulate but what was entirely true was our characterization that no discussions — which [it] somehow was... a wink and a nod to the Canadian government — took place. It turns out yes, Goolsbee was invited over and someone naively didn't understand that what he thought were casual conversations might end up in the memo to the Prime Minister of Canada."

For those people who are consumed by the spectre of illegal immigrants making their way over the border from Mexico by the millions, and there appear to be a lot of such people worrying, it is important to note that "free trade" deals like NAFTA have not only been absolutely devastating to American workers, but to Mexican workers and farmers as well. NAFTA was a catastrophe for Mexico, and only served to exacerbate the problem we already had with illegal immigration. In the final Democratic presidential debate before the Ohio and Texas primaries, we saw Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama practically falling all over themselves trying to outdo each other in criticizing NAFTA and trying to disassociate themselves from it. Were either one of them being the least bit sincere about it at all? Was is sheer political opportunism and false populism on the part of both? Obama was a little late in coming to the anti-NAFTA table for my liking, and despite the Clinton administration's record on this, he wound up getting burned in particular when his University of Chicago economics adviser Austan Goolsbee visited the Canadian consulate in Chicago and basically gave the Canadians a wink and told them to cool it... telling them that Barack was just electioneering, and that he really didn't mean any of this stuff he was saying about wanting to renegotiate NAFTA (as if our problems with NAFTA , the WTO, and free trade deals had much to do with Canada anyway). The Obama campign handled the aftermath badly at first, trying to deny that Goolsbee had met with the Canadians, then trying to claim that he had been taken out of context. Really? Says Obama, "It was truthful based on what we knew at the time. Frankly, none of us were aware that Austan had gone to the Canadian consulate but what was entirely true was our characterization that no discussions — which [it] somehow was... a wink and a nod to the Canadian government — took place. It turns out yes, Goolsbee was invited over and someone naively didn't understand that what he thought were casual conversations might end up in the memo to the Prime Minister of Canada."

I'm not taking much comfort out of that. It sort of took the bloom of the rose for me, as far as Obama is concerned.

What the hell is it with these Democrats? Just who do they think they are supposed to be representing the interests of?

I'd sure hate to throw my vote away and contribute to the election of the Republican candidate by putting a vote in for Ralph Nader, but is it true that he is the only one who really cares about what is happening to working (and out-of-work) Americans, with his Seventeen Traditions?

I'm fed up with offshoring, outsourcing, privatization, the dismantling of government, and the economic gutting of this country for the benefit of a globalized elite who want to accrue everything for themselves at the top. Everyone else, they'd like to force into a race to the bottom.

Cambridge Economist Ha-Joon Chang has a new book out called Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism. It's not a condemnation of capitalism. It is a historical survey on how successful economies have been built around policies that protect national industries, and not on the myth of free trade. From this Business Week review:

Imagine a country where regulation of foreign investment is so strict that noncitizens can't own voting shares of financial institutions. Overseas banks are barred from opening branches. Foreigners can't own the most desirable land. Mining and logging are largely restricted to citizens. Foreign companies are taxed more heavily than domestic ones, and in some jurisdictions they're stripped of all legal protection. China? Some despotic state in Africa? Nope, says Cambridge University economist Ha-Joon Chang, it was the U.S.—in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Those are just the kinds of policies that drive advocates of free trade batty. But in Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism, Chang argues that the policy recommendations of the "unholy trinity" of the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and World Trade Organization would have been unacceptable to the U.S., Britain, Japan, and the European powers when they were industrializing. Instead of helping emerging economies, the free traders—Chang's "Bad Samaritans"—actually do more harm than good.

Chang challenges virtually every tenet free traders hold dear: Patent and copyright protection, privatization, and balanced budgets aren't unalloyed positives, he writes. Tariff barriers, restrictions on foreign investment, inflation, deficit spending, and even corruption, meanwhile, aren't necessarily evil. The material isn't exactly light, and at times Chang gets bogged down in details. But the book presents a well-researched and readable case against free-trade orthodoxy....

...Chang doesn't oppose free trade altogether. He acknowledges that it has plenty of benefits for countries and companies that are ready for global competition. But he argues that not every country should follow the prescriptions of the free traders. Nurturing industries in development (which may take decades), running a deficit to spur investment, and tolerating a measure of inflation to fuel growth, he insists, all have their place—even in a world committed to free trade.

Here, from Thomas Hartmann on Buzzflash:

The fundamental myth of the Milton/Thomas Friedman neoliberal cons is that in a "flat world" everybody is not only able to compete with everybody else freely, but should be required to. It sounds nice. America trades with - and competes with trade with and for - the European Union. France against Germany. England against Australia.

But wait a minute. In such a "free" trade competition, who will win when the match-up is Canada versus the Solomon Islands? Germany versus Bulgaria? Zimbabwe versus Italy?

There are two glaringly obvious flaws in the so-called "free trade" theories expounded by neoliberal philosophers like Friedrich Von Hayek and Milton Friedman, and promoted relentlessly in the popular press by (very wealthy) hucksters like Thomas Friedman.

First, "infant" economies - countries that are only beginning to get on their feet - cannot "compete" with "mature" economies. They really only have two choices - lose to their more mature competitors and stand on the hungry and cold outside of the world of trade (as we see with much of Africa), or be colonized and exploited by the dominant corporate forces within the mature economies (as we see with Shell Oil and Nigeria, or historically with the "banana republics" of Central and South America and Asia and, literally, the banana corporations).

Second, the way "infant" economies become "mature" economies is not via free trade. It never has been and never will be. Whether it be the mature economies of Britain (which began to seriously grow in the early 1600s), America (late 1700s), Japan (1800s), or Brazil (1900s), in every single case, worldwide, without exception, the economic strength and maturity of a nation came about as a result not of governments "standing aside" or "getting out of the way" but instead of direct government participation in and protection of the "infant" industries and economy....

....To illustrate how infant industries must be nurtured by government until they're ready to compete in global marketplaces, Chang points to the example of his own son, Jin-Gyu. At the age of six, the young boy is legally able to work and produce an income in many countries of the world. He's an "asset" that could be "producing income" right now. But Chang, being a good parent, intends to deny his son the short-term "opportunity" to learn a skill like street-sweeping or picking pockets or shining shoes (typical "trades" for six year olds in many countries) so he may grow up instead to become an engineer or physician - or fully reach whatever other potential his temperament, abilities, and inclination dictate.

Somehow this is lost on Thomas Friedman and the whole "free trade" bunch. As Chang writes, "[E]ven from a purely materialistic viewpoint, I would be wiser to invest in my son's education than gloat over the money I save by not sending him to school. After all, if I were right [in sending him out to work at age six], Oliver Twist would have been better off pick-pocketing for Fagin, rather than being rescued by the misguided Good Samaritan Mr. Brownlow, who deprived the boy of his chance to remain competitive in the labor market.

"Yet this absurd line of argument is in essence how free-trade economists justify rapid, large-scale trade liberalization in developing countries. They claim that developing country producers need to be exposed to as much competition as possible right now, so that they have the incentive to raise their productivity in order to survive. Protection, by contrast, only creates complacency and sloth. The earlier the exposure, the argument goes, the better it is for economic development."

But history proves the free-traders wrong. Every time, without exception, a developing nation is forced (usually by the IMF, WTO, and/or World Bank) to unilaterally throw open all their doors to "free trade," the result is a disaster. Local industries, still in their developmental stages, are either wiped out or bought out and shut down by foreign behemoths. Wages collapse. The "Middle Class" becomes the working poor. And in the process the largest corporations and wealthiest individuals in the world become larger, stronger, and more wealthy. It's "Monopoly" (the game) on steroids.

Even worse, opening a country up to "free trade" weakens its democratic institutions. Because the role of government is diminished - and in a democratic republic "government" is another word for "the will of the people" - the voice of citizens in the nation's present and future economy is gagged, replaced by the bullhorn of transnational corporations and think-tanks funded by grants from mind-bogglingly wealthy families. One-man-one-vote is replaced with one-dollar-one-vote. Governments are corrupted, often beyond immediate recovery, and democracy is replaced by a form of oligarchy that is most rightly described as a corporate plutocratic kleptocracy.

When this corporate oligarchy reaches out to take over and merge itself with the powers and institutions of government, it becomes the very definition of Mussolini's "fascism": the merger of corporate and state interests. As China has proven, capitalism can do very well, thank you, in the absence of democracy. (You'd think we would have figured that out after having watch Germany in the 1930s.) And as so many of the Northern European countries show so clearly, capitalism can flourish and generate great wealth and a high standard of living within the constraints of intense regulation by a democratic republic answerable entirely to its citizens.

Corporate globalization cheerleader and WTO shill Tom Friedman, wearing the Moustache of Understanding

More from David Sirota:

Reporters, pundits and lobbyists are insulated from the job and wage cuts that rigged policies such as NAFTA encourage. To them, the profit-making status quo is swell, and so the news they manufacture avoids upsetting those who did the rigging. Consequently, the trade debate is portrayed as a battle between Saint Commerce and evil "protectionists" - a fallacious depiction burying significant questions.

For instance, America became an economic force in the early 20th century thanks, in part, to tariffs sheltering our industries. Considering that, why are all tariffs now billed as inherently bad for the economy and "free" trade billed as inherently good?

Speaking of that word "free" - why does it describe protectionism for corporate profits? "Free" trade deals wrapped in the rhetoric of Sally Struthers ads include no human rights protections. But they include patent protections that inflate pharmaceutical prices. Why does "free" trade refer only to pacts being free of protections for people?

Similarly, why have Washington's "free" traders passed laws blocking Americans from importing lower-priced, FDA-approved prescription drugs from other countries? What is "free" about letting corporations import lead-slathered toys, but barring citizens from importing life-saving medicine?

Trade fundamentalists like Newsweek's Fareed Zakaria say "struggling farmers" abroad want more NAFTA-style agreements. Why then are Mexican and Peruvian farmers now staging mass protests against our "free" trade deals? Could they know our trade policy promotes market-skewing subsidies helping corporate agribusiness put "struggling farmers" out of business?

Finally, what is "free" about trade rules letting international tribunals invalidate domestic laws? As the watchdog group Public Citizen discovered, Democrats' climate and health care proposals could face such challenges at the World Trade Organization.

This epoch of globalization has become an era of media-driven insouciance - one allowing a journalist such as Thomas Friedman to retain his "expert" label while bragging that he "didn't even know what was in" a trade deal he championed. This is a time when the biggest economic deliberations are dominated by commentators berating Democrats for mentioning trade and then falling silent when Republicans praise pacts that eliminate jobs.

-- David Sirota (Hope in the time of NAFTA)

Much has been written about the case of Obama's economic guru, Austan Goolsbee, and the Canadians, but it's worth revisiting in the context of Monstergate. In telling the Canucks to pay no attention to his boss' saber-rattling on NAFTA, Goolsbee was being candid and stating the plain truth: Nobody who knows Obama believes for a second that he is anything but a staunch free trader; they know that he has no intention of trashing the trade treaty. But Goolsbee was also being sloppy. And so was the campaign in its ludicrously transparent, transparently ludicrous efforts to mislead the press about what occurred. (The Canadians contacted Goolsbee not in his capacity as Obama's guy on economics but merely as a University of Chicago academic? As Bill Clinton might put it, Give me a break!) The whole imbroglio fairly reeked of an operation that had become accustomed — too accustomed for its own good — to a sleepy, besotted press corps.

-- John Heilemann (Can Obama Handle the Awakened Media Beast?)

For those people who are consumed by the spectre of illegal immigrants making their way over the border from Mexico by the millions, and there appear to be a lot of such people worrying, it is important to note that "free trade" deals like NAFTA have not only been absolutely devastating to American workers, but to Mexican workers and farmers as well. NAFTA was a catastrophe for Mexico, and only served to exacerbate the problem we already had with illegal immigration. In the final Democratic presidential debate before the Ohio and Texas primaries, we saw Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama practically falling all over themselves trying to outdo each other in criticizing NAFTA and trying to disassociate themselves from it. Were either one of them being the least bit sincere about it at all? Was is sheer political opportunism and false populism on the part of both? Obama was a little late in coming to the anti-NAFTA table for my liking, and despite the Clinton administration's record on this, he wound up getting burned in particular when his University of Chicago economics adviser Austan Goolsbee visited the Canadian consulate in Chicago and basically gave the Canadians a wink and told them to cool it... telling them that Barack was just electioneering, and that he really didn't mean any of this stuff he was saying about wanting to renegotiate NAFTA (as if our problems with NAFTA , the WTO, and free trade deals had much to do with Canada anyway). The Obama campign handled the aftermath badly at first, trying to deny that Goolsbee had met with the Canadians, then trying to claim that he had been taken out of context. Really? Says Obama, "It was truthful based on what we knew at the time. Frankly, none of us were aware that Austan had gone to the Canadian consulate but what was entirely true was our characterization that no discussions — which [it] somehow was... a wink and a nod to the Canadian government — took place. It turns out yes, Goolsbee was invited over and someone naively didn't understand that what he thought were casual conversations might end up in the memo to the Prime Minister of Canada."

For those people who are consumed by the spectre of illegal immigrants making their way over the border from Mexico by the millions, and there appear to be a lot of such people worrying, it is important to note that "free trade" deals like NAFTA have not only been absolutely devastating to American workers, but to Mexican workers and farmers as well. NAFTA was a catastrophe for Mexico, and only served to exacerbate the problem we already had with illegal immigration. In the final Democratic presidential debate before the Ohio and Texas primaries, we saw Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama practically falling all over themselves trying to outdo each other in criticizing NAFTA and trying to disassociate themselves from it. Were either one of them being the least bit sincere about it at all? Was is sheer political opportunism and false populism on the part of both? Obama was a little late in coming to the anti-NAFTA table for my liking, and despite the Clinton administration's record on this, he wound up getting burned in particular when his University of Chicago economics adviser Austan Goolsbee visited the Canadian consulate in Chicago and basically gave the Canadians a wink and told them to cool it... telling them that Barack was just electioneering, and that he really didn't mean any of this stuff he was saying about wanting to renegotiate NAFTA (as if our problems with NAFTA , the WTO, and free trade deals had much to do with Canada anyway). The Obama campign handled the aftermath badly at first, trying to deny that Goolsbee had met with the Canadians, then trying to claim that he had been taken out of context. Really? Says Obama, "It was truthful based on what we knew at the time. Frankly, none of us were aware that Austan had gone to the Canadian consulate but what was entirely true was our characterization that no discussions — which [it] somehow was... a wink and a nod to the Canadian government — took place. It turns out yes, Goolsbee was invited over and someone naively didn't understand that what he thought were casual conversations might end up in the memo to the Prime Minister of Canada."I'm not taking much comfort out of that. It sort of took the bloom of the rose for me, as far as Obama is concerned.

What the hell is it with these Democrats? Just who do they think they are supposed to be representing the interests of?

I'd sure hate to throw my vote away and contribute to the election of the Republican candidate by putting a vote in for Ralph Nader, but is it true that he is the only one who really cares about what is happening to working (and out-of-work) Americans, with his Seventeen Traditions?

I'm fed up with offshoring, outsourcing, privatization, the dismantling of government, and the economic gutting of this country for the benefit of a globalized elite who want to accrue everything for themselves at the top. Everyone else, they'd like to force into a race to the bottom.

Cambridge Economist Ha-Joon Chang has a new book out called Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism. It's not a condemnation of capitalism. It is a historical survey on how successful economies have been built around policies that protect national industries, and not on the myth of free trade. From this Business Week review:

Imagine a country where regulation of foreign investment is so strict that noncitizens can't own voting shares of financial institutions. Overseas banks are barred from opening branches. Foreigners can't own the most desirable land. Mining and logging are largely restricted to citizens. Foreign companies are taxed more heavily than domestic ones, and in some jurisdictions they're stripped of all legal protection. China? Some despotic state in Africa? Nope, says Cambridge University economist Ha-Joon Chang, it was the U.S.—in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Those are just the kinds of policies that drive advocates of free trade batty. But in Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism, Chang argues that the policy recommendations of the "unholy trinity" of the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and World Trade Organization would have been unacceptable to the U.S., Britain, Japan, and the European powers when they were industrializing. Instead of helping emerging economies, the free traders—Chang's "Bad Samaritans"—actually do more harm than good.

Chang challenges virtually every tenet free traders hold dear: Patent and copyright protection, privatization, and balanced budgets aren't unalloyed positives, he writes. Tariff barriers, restrictions on foreign investment, inflation, deficit spending, and even corruption, meanwhile, aren't necessarily evil. The material isn't exactly light, and at times Chang gets bogged down in details. But the book presents a well-researched and readable case against free-trade orthodoxy....

...Chang doesn't oppose free trade altogether. He acknowledges that it has plenty of benefits for countries and companies that are ready for global competition. But he argues that not every country should follow the prescriptions of the free traders. Nurturing industries in development (which may take decades), running a deficit to spur investment, and tolerating a measure of inflation to fuel growth, he insists, all have their place—even in a world committed to free trade.

Here, from Thomas Hartmann on Buzzflash:

The fundamental myth of the Milton/Thomas Friedman neoliberal cons is that in a "flat world" everybody is not only able to compete with everybody else freely, but should be required to. It sounds nice. America trades with - and competes with trade with and for - the European Union. France against Germany. England against Australia.

But wait a minute. In such a "free" trade competition, who will win when the match-up is Canada versus the Solomon Islands? Germany versus Bulgaria? Zimbabwe versus Italy?

There are two glaringly obvious flaws in the so-called "free trade" theories expounded by neoliberal philosophers like Friedrich Von Hayek and Milton Friedman, and promoted relentlessly in the popular press by (very wealthy) hucksters like Thomas Friedman.

First, "infant" economies - countries that are only beginning to get on their feet - cannot "compete" with "mature" economies. They really only have two choices - lose to their more mature competitors and stand on the hungry and cold outside of the world of trade (as we see with much of Africa), or be colonized and exploited by the dominant corporate forces within the mature economies (as we see with Shell Oil and Nigeria, or historically with the "banana republics" of Central and South America and Asia and, literally, the banana corporations).

Second, the way "infant" economies become "mature" economies is not via free trade. It never has been and never will be. Whether it be the mature economies of Britain (which began to seriously grow in the early 1600s), America (late 1700s), Japan (1800s), or Brazil (1900s), in every single case, worldwide, without exception, the economic strength and maturity of a nation came about as a result not of governments "standing aside" or "getting out of the way" but instead of direct government participation in and protection of the "infant" industries and economy....

....To illustrate how infant industries must be nurtured by government until they're ready to compete in global marketplaces, Chang points to the example of his own son, Jin-Gyu. At the age of six, the young boy is legally able to work and produce an income in many countries of the world. He's an "asset" that could be "producing income" right now. But Chang, being a good parent, intends to deny his son the short-term "opportunity" to learn a skill like street-sweeping or picking pockets or shining shoes (typical "trades" for six year olds in many countries) so he may grow up instead to become an engineer or physician - or fully reach whatever other potential his temperament, abilities, and inclination dictate.

Somehow this is lost on Thomas Friedman and the whole "free trade" bunch. As Chang writes, "[E]ven from a purely materialistic viewpoint, I would be wiser to invest in my son's education than gloat over the money I save by not sending him to school. After all, if I were right [in sending him out to work at age six], Oliver Twist would have been better off pick-pocketing for Fagin, rather than being rescued by the misguided Good Samaritan Mr. Brownlow, who deprived the boy of his chance to remain competitive in the labor market.

"Yet this absurd line of argument is in essence how free-trade economists justify rapid, large-scale trade liberalization in developing countries. They claim that developing country producers need to be exposed to as much competition as possible right now, so that they have the incentive to raise their productivity in order to survive. Protection, by contrast, only creates complacency and sloth. The earlier the exposure, the argument goes, the better it is for economic development."

But history proves the free-traders wrong. Every time, without exception, a developing nation is forced (usually by the IMF, WTO, and/or World Bank) to unilaterally throw open all their doors to "free trade," the result is a disaster. Local industries, still in their developmental stages, are either wiped out or bought out and shut down by foreign behemoths. Wages collapse. The "Middle Class" becomes the working poor. And in the process the largest corporations and wealthiest individuals in the world become larger, stronger, and more wealthy. It's "Monopoly" (the game) on steroids.

Even worse, opening a country up to "free trade" weakens its democratic institutions. Because the role of government is diminished - and in a democratic republic "government" is another word for "the will of the people" - the voice of citizens in the nation's present and future economy is gagged, replaced by the bullhorn of transnational corporations and think-tanks funded by grants from mind-bogglingly wealthy families. One-man-one-vote is replaced with one-dollar-one-vote. Governments are corrupted, often beyond immediate recovery, and democracy is replaced by a form of oligarchy that is most rightly described as a corporate plutocratic kleptocracy.

When this corporate oligarchy reaches out to take over and merge itself with the powers and institutions of government, it becomes the very definition of Mussolini's "fascism": the merger of corporate and state interests. As China has proven, capitalism can do very well, thank you, in the absence of democracy. (You'd think we would have figured that out after having watch Germany in the 1930s.) And as so many of the Northern European countries show so clearly, capitalism can flourish and generate great wealth and a high standard of living within the constraints of intense regulation by a democratic republic answerable entirely to its citizens.

Corporate globalization cheerleader and WTO shill Tom Friedman, wearing the Moustache of Understanding

More from David Sirota:

Reporters, pundits and lobbyists are insulated from the job and wage cuts that rigged policies such as NAFTA encourage. To them, the profit-making status quo is swell, and so the news they manufacture avoids upsetting those who did the rigging. Consequently, the trade debate is portrayed as a battle between Saint Commerce and evil "protectionists" - a fallacious depiction burying significant questions.

For instance, America became an economic force in the early 20th century thanks, in part, to tariffs sheltering our industries. Considering that, why are all tariffs now billed as inherently bad for the economy and "free" trade billed as inherently good?

Speaking of that word "free" - why does it describe protectionism for corporate profits? "Free" trade deals wrapped in the rhetoric of Sally Struthers ads include no human rights protections. But they include patent protections that inflate pharmaceutical prices. Why does "free" trade refer only to pacts being free of protections for people?

Similarly, why have Washington's "free" traders passed laws blocking Americans from importing lower-priced, FDA-approved prescription drugs from other countries? What is "free" about letting corporations import lead-slathered toys, but barring citizens from importing life-saving medicine?

Trade fundamentalists like Newsweek's Fareed Zakaria say "struggling farmers" abroad want more NAFTA-style agreements. Why then are Mexican and Peruvian farmers now staging mass protests against our "free" trade deals? Could they know our trade policy promotes market-skewing subsidies helping corporate agribusiness put "struggling farmers" out of business?

Finally, what is "free" about trade rules letting international tribunals invalidate domestic laws? As the watchdog group Public Citizen discovered, Democrats' climate and health care proposals could face such challenges at the World Trade Organization.

Saturday, March 01, 2008

Fr. Howard Gray SJ, on Choosing out of Compassion

A Lenten Retreat based on Mt. 9:36 and Mt 11:29

My parish recently hosted a mini-retreat which was led by the Rev. Howard J. Gray, SJ.

My parish recently hosted a mini-retreat which was led by the Rev. Howard J. Gray, SJ.

Fr. Gray is currently the Assistant to the President for Special Projects at Georgetown University. He has also served as the Rector of the Jesuit community at John Carroll University, as Associate professor of Spiritual Theology and Rector of the Weston Jesuit School of Theology, and the Jesuit Provincial for the Detroit Province. He has also taught and lectured at Boston College and Fordham University.

Since I've become sensitized to the issue, I've become increasingly uncomfortable and impatient with interpretations of Christianity which need to characterize Judaism as a legalistic, burdensome religion. I don't feel a need to denigrate another religion in order to lift up my own, particularly the religion of Jesus himself. I'm not saying that Fr. Gray was doing this, but I think he's hanging onto some interpretations that are becoming increasingly outdated. Nevertheless, I think there was a lot that was valuable to be taken out of his presentation. My notes:

The theme is compassion. The first approach is to look at how the Lord shows compassion, and then at how we show compassion.

Passion is a peculiar word. There is sexual passion, and emotional passion, emotions stirred by words or ideas. The Church speaks of passion as in the case of the Passion narrative, but also in the words of our Lord. Christ gathered in his heart the experiences of those around him, and we speak of passion in the sense of how this moved him. It speaks of the very human way in which he received all the data about his people from his Father, and translated it for the rest of his life. People wanted to lead a better life, but were trapped. He knew that there were people on the borders, broken-hearted, who wanted to be invited in. This was the data that God was giving him through the people among who he lived. In his own community, he was so mingled among the human that he lost himself in the human.

In the Gospel of Matthew we see summary statements of what the people around him were like. They were sheep without shepherds. To Israel, God is like a shepherd (23rd Psalm). That is what Israel thought God should be to it. The shepherd metaphor had immediate and practical, familiar meaning to them. Jesus sees them wandering, getting lost, and perishing. They were not doing bad things. They were good people, many who could not read or write, who did not know all the laws, worked hard during the day, even to the point of not having a place to wash their hands (with the result of not being able to follow all of the laws completely). On the one hand, they felt no release from Roman oppression. On the other, they had no time for education to follow the laws perfectly. They had love for temple worship, but yearned for it more deeply. Much of the message of Jesus is the bringing of the fullness of life to people in his own tradition. Jesus learned it himself by watching them, listening to them, and hearing their hearts. Not only in listening to them and being formed by them, but their hunger was in some way his hunger. He was searching and questioning too. He was with them. “Who do people say that I am?” The question was real, and came from his own heart. “What do you see?” We don’t claim that “Jesus was like us in all things but questions.” He understands us as he understood them. Com-passion. He knew their hunger, as an itinerant preacher. He was in the fields, the villages, and the towns. He was where the people were. He fed their hunger, thirst, and tiredness.

In Luke, we see a description of this activity. He eats a lot (the Ministry of Hospitality – “Table Ministry”). Eating a meal is a chance for exchange. When you ate a meal with someone, it rubbed off on you. You became one of their family. Examples are see in the parables of:

- The Lost Coin and the Widow

- The Lost Sheep and the Shepherd

- The Prodigal Son

In all, we can see Jesus realizing “They need me.” They need to know that no matter what they’ve done, they will be loved. He deepened his understanding of family life, and of friendship, and of caring. These are people too poor to pay the Temple Tax. The Romans were taking almost all from them with taxes of their own, and the inability to pay the Temple Tax was making them feel like 3rd class or 4th class religious citizens.

As for the rich, there were two kinds. Those showing off, and those who realized how poor they really were. In the story of Simon and the woman with the alabaster jar, where Jesus is invited to eat at the home of a rich man, we see an example of the rich “slumming.” On the other hand, we have the story of Zaccheus. A shrimp whom no one had ever bothered to treat seriously, before Jesus did.

Jesus did his ministry while walking. It was not formalized. He meets worlds that he never met before, such as the gentile world, the Samaritan world, and the sinful world. For example, Joseph and Mary’s world was not a bad world, but it was a careful world. Mary would not have met with prostitutes, and we see evidence that the family of Jesus was somewhat confused and worried about his actions. Jesus was reaching out to people who were being too quickly written off as being beyond the reach of God.

Jesus was speaking with authority. It came from inside, from someone who felt the impact of his own words. He spoke of God as “Abba”, a beloved father. He was talking from his heart.

The mark of humanity is being born into restriction (Rahner?). We are limited, but his disciples recognized him, and even crucifixion and death could not change that. At the age of 77, we are not like we were at the age of 27. We change. We learn as we walk through life. Through weaknesses and mistakes, we become wiser. Jesus spoke of the Kingdom of God being at hand. From him there was a renewed sense of urgency and availability. Part of the reason why he was killed was because he made religion too available. The people of his time considered God to be transcendent. To be transcendent, however, does not mean being remote or distant. It means that he is more than what we think he is. More loving, more forgiving, more compassionate.

Jesus announced that the Kingdom of God had begun. It is in your hands. The Kingdom is both within your grasp and still yet to be fulfilled. Both notions are held up to skepticism in the world in which we live. Religion is now being held up as the prime cause of fanaticism and wars. Religion, of course, can be misused just like money, property, and learning can. That is the nature of free will. Our freedom also gives us the ability to love. Love cannot be forced. Our Lord understood freedom. Sometimes he was angry, sometimes he mourned, but mostly his inclination as to invite. In John: “What are you looking for?” “Master, where do you live?” “Come and see.”

In Luke, the same truths are there. “What is the greatest commandment if one is to inherit the Kingdom of God.” “Love your neighbor.” “Who is my neighbor?”

The Good Samaritan (After Delacroix),

by Vincent van Gogh (1890)