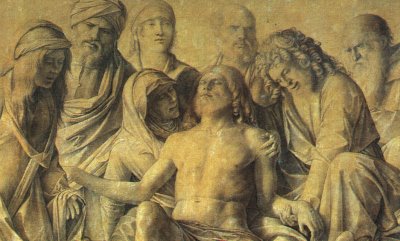

The Lamentation over the Body of Christ by Giovanni Bellini, c. 1480-1500

When the sex abuse scandal broke upon the Church in Boston five years ago, falling on us like a mighty wave, the pastor of my parish invited people to gather together and feel free to vent and to talk about it. Those sessions led to the birth of the VOTF, which was formed at that very same parish. I know a lot of the founders. I've worked in parish ministries with quite a few of them. They are very good people, and for them, the formation of a group that would really work to put survivors first was a paramount concern. They are to be lauded for working closely in the healing process with many of the survivors of clerical sexual abuse to this very day. In addition, there was a issue of credibility at stake. These are people who love the Church and want to be able to look their children and grandchildren in the eye and say that they tried to do something about this... that they just didn't roll over and say that everything is going to be fine.... That they did do everything they could to make sure that children were going to be safe. They are still demanding accountability on the part of the bishops, because as we've seen, things can all too easily fall back into the status quo if nothing is done to challenge them.

In July of 2002 the VOTF held their first annual convention at the Hynes Auditorium in Boston and were pleased and very proud to have over 4,200 people attend, especially in light of the fact that the group was only a few months old.

Something instructive, however, happened almost exactly a year later. Someone noticed what looked like an image of the Virgin Mary on a window at Milton Hospital and over 25,000 people showed up over the next few weeks to take note of it and to pray there.

Now, I have a profound love and appreciation for the BVM as many Catholics do, but like many of the the sophisticated, well-heeled suburbanites in the VOTF, I find this kind of Marian excessiveness commonly found within Catholic ranks to be embarassing and hard to defend or excuse.

On the other hand, is it really me who's missing something here, whether you can brand this as superstition or not? Milton Hospital eventually took over $14,000 in unsolicited contributions to the hospital left by the crowds and offered it as Gulf Coast hurricane relief, ironically, to the Salvation Army.

Most VOTF members tend towards the liberal and progressive side. I've been to enough of their meetings and heard enough emphasis being placed upon the necessity for women's ordination and so forth to know that is the case. That's fine, but this post really isn't about the VOTF... The point is this... The liberal critique is missing something vital. There is a need out there that is not being met. Pastoral associates, catechists, and liturgists don't always seem to have their finger on the pulse of what drives and motivates the spiritual life of a great many people.

In this column by Fr. Ron Rolheiser, he makes note of some observations made by the late Raymond Brown.

Those parishes and worshipping communities that most stress good theology and proper liturgy as a healthy corrective to privatized and devotional spirituality, often find they are losing parishioners to religious groups that stress a personal relationship to Jesus, that is, groups that come out of old-style Roman Catholic devotions or out of Protestant, "born-again" fundamentalism. Mainline pastors argue that this is not a healthy development and state, correctly, that liturgical worship should be the central piece to any ecclesiology and spirituality. But they are also learning communal worship alone, even when done with the greatest attention to proper ritual can lack something -- an accompanying personal spirituality.

Jesus needs a personal face and those conducting liturgy must help the community to know that face, otherwise liturgy alone leaves the community wanting for something. Brown goes on to suggest mainline Christians sometimes speak of "born-again Christians" pejoratively, suggesting that their stress on a privatized, salvific relationship to Jesus is not healthy. However, Brown suggests that the evangelist John might ask the mainline churches (and our liturgists and theologians) to be a little more sympathetic towards our devotionally-oriented and "born-again" siblings because, for John, Church membership alone is not a sufficient goal and liturgy is adequate only when it also helps effect a personal, affective relationship to Jesus.

Annie Dillard makes this comment: Sharing why she worshipped in a fundamentalistic, sectarian church (when her natural temperament was towards Roman Catholicism or high-church Protestantism) she replies: I go to that particular church because I like the minister. He actually believes what he preaches and when he says a prayer, he really means it."

Implied in that, sadly, is the comment that, in our high churches, that is not always so evident of those reading the word, leading the prayers, conducting the music and doing the preaching. I want to say this sympathetically, as Brown did, and yet not mute its challenge: For those of us who are "high church," either by temperament or denomination, it's too easy to look at the devotional stream within Roman Catholicism or the "low church" tradition within Protestantism and see it simply as "Jesus and I" spirituality, as excessively privatized, as seeking the wrong kind of security, as spiritually immature, as theological and liturgical backwater, and as deflecting people from the real centre, worship in liturgy.

In making such an assessment, partially, we are dangerously wrong, at least according to one New Testament writer.

In John's Gospel, ecclesiology and liturgy are subservient to the person of Jesus and a personal relationship to him. To teach this, John presents the image of "the beloved disciple," one who has a special intimacy with Jesus. For John, this intimacy outweighs everything else, including special service in the Church.

At the end of the day, Christianity must be about a real encounter with a person - the Divine Person of Jesus Christ.

Elsewhere, Rolheiser has written:

What is the Achilles heel in liberal Catholicism? One place where liberal Catholicism might want to do some self-scrutiny:

On our failure to inspire permanent, joyous religious commitment. Cardinal Francis George, speaking at a Commonweal magazine coloquium, said, "We are at a turning point in the life of the Church in this century. Liberal Catholicism is an exhausted project. Essentially a critique, even a necessary critique at one point in our history, it is now parasitical on a substance that no longer exists. It has shown itself unable to pass on the faith in its integrity and is inadequate, therefore, in fostering the joyful self-surrender called for in Christian marriage, in consecrated life, in ordained priesthood."

This is not a comment that goes down well with everyone, especially with those of us who have given the best part of our lives struggling to open our churches up to a healthier, less-fearful relationship with modernism, science, secularity, and the real moral progress these have helped to bring to the world.

But George's comment strikes at a particular painful area. For all of our work at spreading the democratic principle, highlighting the plight of the poor, working at eliminating racism, pushing for gender equality and furthering ecological sensitivity, we haven't been able to inspire our own children to follow us in the faith path. It's something we must examine ourselves on.

There may be something to that. At the turn of the Twentieth Century, Mainline Protestantism went through something similar. It put a heavy emphasis on the social gospel, probably right in doing so, but suffered from a fundamentalist backlash that has since thinned their ranks considerably.

One VOTF member remarked to my wife recently that the only people who seem to care about what they are trying to accomplish are over 60. There may be some truth in that. When I look at Catholic blogs, the traditionalist sites seem to outnumber the progressives by about 20 to 1. For Protestant sites, it looks similar to me. Young people are looking for what they regard as "authenticity". They are looking for people who appear to really mean what they say.

Columist Muriel Porter has a take on it that brings the effects of secularism into play here in her article Vulnerability of the post-Christian generation:

The mainstream churches wring their hands in despair, but some of the blame clearly belongs with them. While the lives of women in particular and families in general have changed dramatically since the 1960s, the churches by and large have failed to listen, let alone lead.

The Catholic Church's blanket ban on artificial contraception, the Anglican Church's hard-fought but only piecemeal concessions to female equality, all the churches' resistance both to more fluid family structures and to homosexual partnerships, have combined to give Christianity a gloomy, life-denying, out-of-touch image. There has been no great temptation for secular people to seek the God the Christian churches preach.

Our secular society's addiction to consumerism, gambling and large-scale debt comes at a high price. The statistics on suicide, depression, family break-up and dysfunction all indicate deep, long-term insecurity and unhappiness.

When disillusionment sets in, people often long for a spiritual dimension in their lives, and so become easy prey for fundamentalist Christian groups with their slick marketing techniques and pseudo-contemporary, music-focused programs. With no religious background to provide the tools for discernment, they are readily swayed by the clear certainties and the harsh take-it-or-leave-it morality preached by charismatic authoritarian male church leaders.

It is no coincidence that the Pentecostal churches and the fundamentalist sections of mainstream churches are drawing large numbers of converts from the very generations who missed out on even a rudimentary Christian education - people ranging from teenagers to the early middle-aged. For a sizeable proportion of these young converts, however, disillusionment will inevitably set in once more. They will eventually chafe under the uncompromising ... teaching and reject it completely. But without an earlier religious background to provide perspective and suggest alternative approaches, they will reject all of Christianity with it. A bitter cynicism and deeper malaise will result.

And there is another sad result of secularisation. A culture without a religious story is fragile and rudderless when it comes to death. People with a residual belief in God but no coherent religious framework are often left floundering when tragedy strikes. Without familiar holy places, they resort to making shrines of the actual sites of death. Homely memorials now dot our highways, or the sites of suicides. Memorial plaques speak vaguely of God, but lack the hope and peace that earlier generations - ironically much more deeply affected by sudden and tragic family deaths - drew from their faith.

As a case in point, look a the number of Latin Americans who have left the Catholic Church for Pentecostalism in recent decades. The New York Times recently ran a four-part series on it. All too often, nominal, cultural, half-catechized Latin American Catholics have been lured away, and why should it be surpising? Who can blame them? We've failed them horribly, particularly by insisting on worshipping at the altar of mandatory priestly celibacy. They have not left because the Catholic Church is too conservative or inflexible. They have left for a faith that is far, far more conservative. A faith that makes it very clear what is expected of them with simple, uncomplicated doctrines. For those who were once gangbangers, addicts or alcoholics wearing a gold crucifix for no apparent reason, their new faith has challenged them to straighten out their lives, recover their dignity and self respect, and to spread that to others. In one of the New York Times articles, we read about the family of a convert named Mr Romero:

His wife, Esperanza, took longer to let go of her Roman Catholicism, particularly the room she had filled with statues of saints — worthless idols, according to Pentecostals, who believe that people should pray directly to God. Mr. Romero persuaded his wife that the statues had to go.

“I went in that room with a hammer, and I broke every saint that was there,” he recalled. “I smashed a table, a fountain full of water, an expensive one. I broke it all. I tied it up in a bag and tossed it in the farthest dump.”

He paused at the memory. “And nothing happened to me.”

What kind of folk religion taught him that something was supposed to happen to him for smashing plaster statues?

I'm not advocating that we respond by becoming as fundamentalist as those who would prosletyse us. What I am saying is that perhaps some of us of a progressive bent have become too clever for our own good, that some of our knowledge-seeking can be for adornment, and that maybe we should do a better job of respecting the simple (healthy) piety around us - to recognize the real human need for Christ that lies in depths of the hearts of all of us, and commonly manifests itself in ways that don't require a PhD. We shouldn't write if off as "adolescent faith." Nature hates a vacuum, and so does the universe of faith. If we don't show that proper respect and appreciation, then superstition and syncretism can be one risk we run and fundamentalism the other.